Issue 5.7: Elden Lore, Part 3

The Outer Gods and the Politics of Magical Opposition in Elden Ring [A Narrative, Historical, Religious, and Metaspiritual Analysis]

Game & Word Volume 5, Issue 7: Friday, Aug. 29th, 2025

Publisher: Jay Rooney

Author, Graphics, Research: Jay Rooney

Logo: Jarnest Media

Table of Contents

Summary & Housekeeping

Feature: “Elden Lore, Part 3” (~56 minute read)

Food for Talk: Discussion Prompts

Further Reading

Game & Word-of-Mouth

Footnotes

Summary:

[PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Wow, it’s been a while, hasn’t it? Apologies for the extended absence; it’s been a very hectic time in my life. Family life needs my attention, and I’m also in a bit of a transitionary period, job-wise. Please understand that all of this must take priority.

I know I’ve announced and teased quite a bit of content, and I’m still working on it. It’ll just have to come out on its own time. The exception is the podcast interview from GDC, as unfortunately, the audio is corrupted. But I’ll keep the rest of the posts coming, slowly but surely.

I appreciate y’all’s patience. For now, please enjoy the next installment of my Elden Ring analysis (as well as a bonus section for paid subscribers!). As always, thank you for your readership. ~J]

We've spent the last two installments examining how power shapes spiritual legitimacy in Elden Ring, first through the Golden Order's theological monopoly, then through the Academy of Raya Lucaria's stranglehold on magical knowledge. Both institutions maintain control through rigorous gatekeeping, by defining what's permissible while suppressing everything else as dangerous heresy.

But here's the thing about totalitarian spiritual regimes: they never quite manage to stamp out all opposition. For every orthodoxy, a dozen heresies spring up. Every approved channel of divine power spawns underground currents that flow in defiance. And in the Lands Between, these alternative paths to power manifest through the influence of the Outer Gods: entities that exist beyond the Greater Will's cosmic jurisdiction and offer their own brands of salvation, transformation, or annihilation.

Each of these paths constitutes an attempt to answer the fundamental question of who gets to define reality itself. Because when the Golden Order declares certain practices heretical, or when the Academy seals away forbidden knowledge, they're not just protecting people from danger (though this is a convenient side effect). They're protecting their own monopoly on truth.

The various factions we'll examine today represent different answers to that monopoly, among them: blood cultists who find divinity in violence and transgression, madmen who preach the gospel of primordial chaos and destruction, utopian dreamers who promise a gentler world, dragon communers who trade humanity for power, lunar conspirators who would tear down the whole system just to see what sprouts from the rubble… and a few more, for good measure.

Sound familiar? It should, and not just because these are recognizable fantasy tropes; they're actually the same patterns of rebellion and revolution that have played out across human history whenever spiritual authority became too concentrated, too rigid, or too overbearing. The Lands Between might be fictional, but its religious conflicts mirror our own world's bloodiest theological disputes with uncanny precision.

So strap in, Tarnished, as we map out Elden Ring’s bloody and adversarial theological landscape!

~Jay

Previous Issues

Game & Word’s most recent issues (currently, all of Volume 5) are available to all, free of charge.

Older issues are currently archived and only accessible to paid subscribers. If you haven’t already, consider upgrading your subscription here:

Volume 1 (The Name of the Game): Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Issue 4

Volume 2 (Yo Ho Ho, It’s a Gamer’s Life for Me): Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Bonus 1 ● Issue 4 ● Issue 5 ● Issue 6 ● Issue 7 ● Bonus 2 ● Issue 8 ● Bonus 3

Volume 3 (Game Over Matter): Intro ● Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Podcast 1 ● Issue 4 ● Video Podcast 1 ● Bonus 1 ● Issue 5 ● Podcast 2 ● Issue 6 ● Issue 7 ● Issue 8 ● Issue 9 ● Podcast 3 ● Bonus 2

Volume 4 (Tempus Ludos): Intro ● Issue 1 ● Video Podcast 1 ● Video Podcast 2 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Issue 4 ● Issue 5 ● Podcast 1 ● Issue 6 ● Issue 7 ● Issue 8 ● Issue 9

Volume 5 (AbraCODEabra!): Intro ● Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Issue 4 ● Issue 5 ● Issue 6

Feature: Elden Lore, Part 3

🚨🚨🚨 SPOILER ALERT 🚨🚨🚨

This series (including this post) contains MULTIPLE huge, bigly, and absolutely GINORMOUS story, lore, thematic, and visual SPOILERS for Elden Ring, including the late game, multiple endings, and its recently released DLC, Shadow of the Erdtree. We’re digging deep here, and almost no stone will be left unturned. You've been warned!

⚠️⚠️⚠️ SQUICK ADVISORY ⚠️⚠️⚠️

Elden Ring is an M-Rated game, and one that sprang from the twisted minds that gave us Dark Souls and Game of Thrones. Some of the events and themes we discuss are very dark, bloody, and gory. So if you’re squeamish, exercise caution before reading ahead.

📛📛📛 WARNING: THIS POST CONTAINS EM DASHES [—] 📛📛📛

Lately, a cadre of annoying, galaxy-brained, pseudointellectual tryhards have taken to shouting “dUrRrR, tHiS iS Ai GeNeRaTeD!!1!” at any post that contains an em dash. As someone who’s been liberally using em dashes since way before ChatGPT was even a thing, this annoys me to no end.

So yeah, this post contains plenty of em dashes. If this bothers you, then quite frankly, piss off. I don’t want to hear it. Mentioning this will get you instantly permabanned.

Charles Dickens and Emily Dickinson’s works are jam-packed with em dashes—do you think those were AI-generated as well? Seriously, go read a book. No, Tony Robbins and Norman Vincent Peale don’t count.1

💡💡💡 POINT OF CLARIFICATION 💡💡💡

To more easily distinguish between “stage” magic and “for realsies” magic, most practitioners spell the latter with a “k” at the end, as “magick.” I prefer to spell it all as “magic,” without the “k”.

So just remember, if you’re confused as to which kind of magic I’m referring to, it’s the supernatural kind unless I specifically say otherwise.

HALT! ✋🏼🛑⚠️

Noble Tarnished, if thou missed Parts 1 and 2 of this hitherto series, I strongly beseech thee to read them, so thou couldst at least attempt to maketh some sense of mine analysis today. So, be sureth to catch thee up before reading further:

Part 3: The Outer Gods and the Politics of Magical Opposition

"The mother of truth desires a wound."

~Bloodfiend’s Sacred Spear (item description)

"We have made God in our image, and we shall suffer for it until we remake ourselves in His—or admit that the image itself is the problem."

~Gerald of Wales (Medieval chronicler), writing about the Cathars (c. 1200 CE)

In Part 1, we dove deep into how the Golden Order enforces order and orthodoxy in the Lands Between. You’ll recall, however, that their stranglehold on the realm’s metaphysical landscape is far from complete or absolute.

In fact, there are several factions that exist outside the purview of the Golden Order, and most of these are actually directly oppositional to the Erdtree and its vision of order and truth. These groups usually (though not always) unite around different Outer Gods that are jockeying against both each other and the Greater Will itself for dominion over the Lands Between.

So let’s take a look at them, all the particular idiosyncratic ways they defy the Golden Order, and what their methods say about their true nature and competing visions for how they’d rule (or destroy) the Lands Between. We’ll also examine how this endless dance between orthodoxy and heresy mirrors similar dynamics in our own world.

The Outer Gods: Unorthodox Sources of Divine Power

Before we dive into each specific faction, we need to understand what exactly the Outer Gods are, and why they matter so much in the game's cosmology.

Unlike the Greater Will, which established itself as the supreme divine authority through the Elden Ring and the Erdtree, the Outer Gods represent alternative sources of cosmic power that exist beyond the current regime’s control.

Think of it this way: if the Greater Will is the Lands Between's equivalent of the Abrahamic God—singular, authoritative, and demanding exclusive worship—then the Outer Gods are the old gods that Christianity tried to stamp out, and the folk spirits that survived beneath the veneer of conversion.

They’re all the alternative cosmologies that promise different paths to transcendence (i.e., everything else that refuses to go away).

Some offer power through blood sacrifice, others through madness or transformation. But each represents a fundamental challenge to the Golden Order's claim that there's only one legitimate path to the divine. That is the through line connecting them all.

And it’s not just their existence that particularly threatens the status quo, it's more that they actively empower their followers. While the Golden Order demands submission to earn Grace, and the Academy of Raya Lucaria requires years of study to unlock sorcery, the Outer Gods tend to be more... generous with their gifts.

Mohg doesn't need to spend decades in seminary to channel the Formless Mother's blood magic, and the Three Fingers don't require a doctorate in theology before granting the power to burn everything to ash. This accessibility makes them especially attractive to those excluded from orthodox channels of power: the desperate, the destitute, the downtrodden, and the thoroughly pissed off.

The game never fully explains where the Outer Gods come from or what they ultimately want, and that ambiguity is crucial to their role in the narrative. They're unknowable forces that remind us how little the Golden Order actually understands about the cosmos it claims to represent.

And each faction aligned with an Outer God is essentially making a bet that their patron's vision of reality is more accurate—or at least more appealing, or more actionable—than the Greater Will's.

The Bloody Fingers and the Formless Mother

"Welcome, honored guest, to the birthplace of our dynasty!"

~Mohg, Lord of Blood

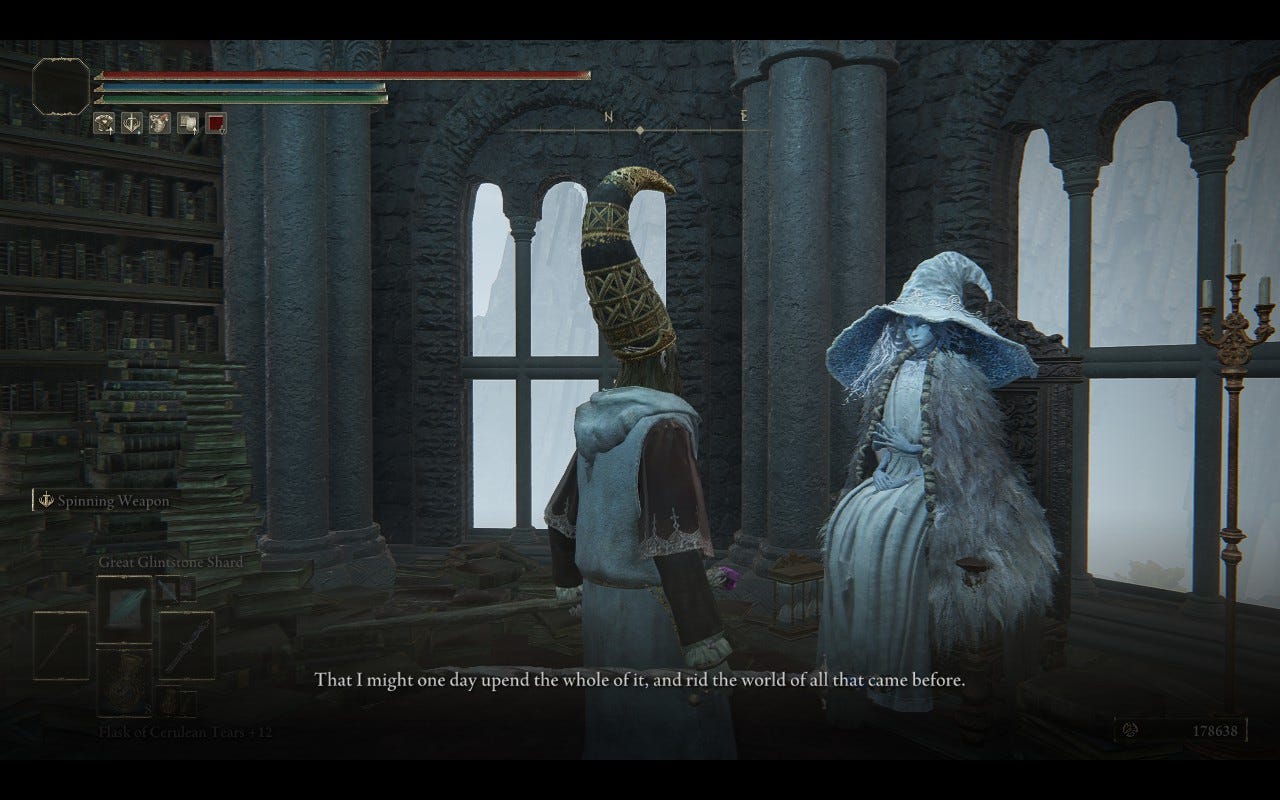

Let's start with perhaps the most viscerally disturbing of the heretical factions: The Bloody Fingers, Mohg's blood cult. Hidden beneath the earth in the nightmarish Mohgwyn Palace, the Lord of Blood has created a separate religious order centered on ritual bloodshed and the worship of the Formless Mother, an Outer God who finds divinity in wounds and hemorrhage.

Mohg himself is a fascinating case study in how subjugation breeds extremism. Born an Omen—one of those cursed beings we touched on in Part 1, reviled and imprisoned by the Golden Order because, like Those Who Live in Death, their very existence flies in the face of their claims of perfection—he spent his youth chained in the sewers beneath Leyndell, despite his noble and divine lineage as one of Queen Marika’s demigod children.

When your entire existence is defined by exclusion from divine grace, is it any wonder you'd turn to another path towards said grace? The Formless Mother didn't care that Mohg had horns! She saw his suffering, his rage, his blood… and said, "Yes, this will do nicely."

The blood magic that Mohg and his followers practice is deliberately transgressive. Where the Golden Order's miracles heal and protect, bloodflame incantations wound and corrupt. And while orthodox faith emphasizes purity and order, the Bloody Fingers revel in contamination and chaos.

They literally strengthen themselves through bloodshed—both their own, and that of their enemies. They attain divine power through violence, and sanctify themselves by slaughtering innocents—though they tend to prioritize targeting Tarnished, albeit for mostly practical reasons, because since any Tarnished has the power to mend the Elden Ring and become Elden Lord, each living Tarnished is a direct threat to Mohg’s designs for his new order.

And with that, we get at what’s actually subversive about Mohg's cult: it's not just the blood, it's about creating a dynasty that will rival the Golden Lineage. Mohg has kidnapped Miquella, the most powerful of the Empyrean demigods, and is attempting to raise him as his consort to establish a new age under the Formless Mother's blessing.2

So he's not trying to destroy the system, he's trying to replace it with his own blood-soaked alternative. The Mohgwyn Dynasty would be everything the Golden Order isn't: welcoming of the cursed, powered by sacrifice rather than grace, and ruled by those the current regime considers abominations.

This actually mirrors something we see repeatedly in real-world religious conflicts: the subdued heretics don't always want to tear down hierarchies—sometimes they just want to be on top of them. Mohg isn't interested in liberation for all Omens. No, he's interested in becoming the god-king of a new order where blood, not gold, determines divinity.

🩸🫀🔮 SIDE QUEST: Blood, Sweat, and Smears

The horror that mainstream religions feel toward blood magic isn't arbitrary. Blood has always occupied a unique position in human spirituality, being simultaneously sacred and profane, purifying while polluting.

So understanding why blood magic is so universally taboo, yet so stubbornly and persistently practiced, tells us something fundamental about how religious authority defines and defends its boundaries.

In the pre-Christian Mediterranean, blood sacrifice was central to religious practice. The Mithraic mysteries, popular among Roman soldiers, involved baptizing initiates in the blood of a sacrificed bull in a ritual called the taurobolium.

The connection between blood and divine favor was explicit and visceral—you literally bathed in life force to achieve spiritual transformation. And these weren't fringe practices; they were state-sanctioned religions with massive followings.

Cleverly, early Christianity sublimated this blood obsession into metaphor: the Blood of Christ saves you, yes, but you don't need actual blood anymore, just wine and faith.3

Nevertheless, the old blood practices never truly disappeared. They just went underground, became folk magic… and transformed into accusations. The medieval blood libel (the persistent and false claim that Jews murdered Christian children for their blood) thus weaponized Christian anxiety about blood sacrifice.

This accusation was Freudian projection of the highest order: Christians, whose central sacrament involved symbolically drinking their god's blood, accused others of the literal blood consumption they had supposedly transcended. And so, the blood libel became a tool of persecution, justifying pogroms and expulsions across Europe.

Meanwhile, actual blood magic persisted in the shadows. Medieval grimoires are full of rituals requiring blood (usually the practitioner's own, pricked from the finger) to sign pacts or activate sigils.

Menstrual blood, in particular, held special power in folk traditions. Here was blood that flowed without violence, connected to lunar cycles and the creation of life itself. The Church found this particularly threatening, because women's bodies could produce magical substance, monthly, without any need for priests or sacraments.

No wonder, then, that midwives and wise women who worked with "women's mysteries" faced such targeted persecution during the witch trials!

And while blood magic’s associations with violence or contamination were enough to render it taboo, it was its egalitarianism that made it so threatening.

Anyone could bleed, which meant anyone could offer sacrifice. You didn't need education, ordination, or even belief. You just needed a sharp edge and the will to use it (or, alternatively, a working uterus). Blood magic thus bypassed institutional gatekeeping entirely, offering direct transaction with divine forces.

The Church's response shouldn’t be surprising to you by now: it monopolized legitimate blood sacrifice through the Eucharist, while suppressing all other blood practices. Only Christ's blood had saving power, and only priests could invoke it. Everyone else's blood was just blood—or worse, a vector for demonic influence.

This created a theological paradox that persists today: Christianity is built on blood sacrifice but simultaneously condemns it, drinks symbolic blood but abhors literal blood rituals, and preaches that blood saves while insisting that seeking salvation through blood is damnable.

Today, contemporary occultism has inherited this complicated relationship with blood magic. Modern practitioners generally discourage blood sacrifice, partly for ethical reasons but mostly for safety (both physical and legal).

Yet, the fascination persists. Blood still appears in contemporary grimoires, usually with careful warnings and suggestions of alternatives. The idea that blood contains life force that can charge sigils or seal pacts remains potent in the occult imagination, even if its actual practice is relatively rare.4

The Frenzied Flame Adherents

“If you inherit the Flame of Frenzy, your flesh will serve as kindling and the girl can be spared... setting you on the righteous path of lordship. The path of the Lord of Chaos.

Burn the Erdtree to the ground, and incinerate all that divides and distinguishes.

Ahhh, may chaos take the world! MAY CHAOS TAKE THE WORLD!”

~Shabriri

Unlike Mohg, who agitates for organized heretical rebellion with the aim of supplanting the current order with his own, Shabriri and the Three Fingers represent something far more radical: complete cosmic nihilism dressed up as liberation theology.

The Frenzied Flame doesn't want to reform the system or replace it. No, it wants to burn everything back to primordial unity—before distinction, before suffering, and before existence as we understand it.

The theology of the Frenzied Flame is deceptively simple: suffering exists because of distinction. The moment the One Great became many, pain entered the world. Every border, every definition, every separate self is a wound in the cosmos.

The only cure is cauterization: burn it all away until nothing remains but the original undifferentiated chaos. It's Buddhism's escape from Samsāra, by way of nuclear holocaust.

Shabriri, the prophet of this apocalyptic vision, is himself a walking violation of natural order. He inhabits the corpse of Yura, a samurai who died hunting Bloody Fingers—an ironic possession that turns a hunter of heretics into the ultimate heretical preacher.

When you meet him, he doesn't try to convince you with complex theology or promises of power. He just points out the fundamental truth that makes the Frenzied Flame so seductive: everyone suffers, and the world is clearly broken. Wouldn't it be merciful to just... end it?

And that’s not even what makes the Frenzied Flame so particularly insidious. Rather, it’s how it spreads. Those afflicted with madness don't just go insane—they become evangelists, their empty eye sockets exploding with yellow flame that inflicts madness on everyone nearby.

It's a contagion of enlightenment, spreading the terrible truth that existence itself is the problem.

The Frenzied Flame first entered the Lands Between through the Nomadic Merchants who were buried alive in the catacombs beneath Leyndell. Persecuted and exterminated for the crime of existing while being different, they called out from their underground coffin in despair, and in doing so, summoned the Three Fingers into the world. Their suffering thus became a beacon for cosmic annihilation.

The Frenzied Flame ending is the only one where you don't become Elden Lord—you become the Lord of Frenzied Flame, which is something altogether different.

You don't rule over the Lands Between; you preside over its cremation.

Uncharacteristically for FromSoftware titles, the game repeatedly warns you not to pursue this path. Should you do so anyway, Melina—your maiden guide who's unconditionally supported you since the very start of your journey—abandons you in horror and vows to kill you.

Even in a game full of moral ambiguity, the Frenzied Flame is presented as unambiguously catastrophic.

Yet the game also makes it disturbingly sympathetic. After all, when you see the piles of merchant corpses, and understand the depth of suffering that summoned this cosmic death wish into being… can you really blame them for wanting it all to end?

🤪🙏🏼☦️ SIDE QUEST: Mad Lads and Saintly Schizos

And now, it’s time dive into the connection between madness and divine truth—one of religion's most persistent and uncomfortable themes.

Across cultures and centuries, those who claim direct contact with the divine often appear insane to conventional society—and sometimes, they actually are. The line between prophet and madman, or between mystical experience and psychotic break, is far thinner than most religious institutions care to admit.

The Eastern Orthodox tradition of "holy fools" (yurodstvo) represents perhaps the most formal acknowledgment of sacred madness. These individuals deliberately acted insane—walking naked in winter, speaking in riddles, and disrupting church services, among other zany antics—as a form of spiritual practice.5

By rejecting social norms and rationality itself, they claimed to access divine truth unavailable to those bound by conventional thinking. The holy fool could therefore criticize princes and priests with impunity, because their madness gave them license to speak uncomfortable truths that would’ve been treason coming from sane lips.

Nevertheless, these figures have always aroused tension. The Russian Orthodox Church tried to manage this tension by simultaneously venerating and trying to control holy fools, establishing criteria to distinguish genuine divine madness from mental illness or charlatanism.

The problem, of course, is that no such criteria can really work. After all, how do you even test if someone's madness is sacred? And how do you go about regulating deliberately irregular behavior?

Meanwhile, further out west, Medieval Europe saw periodic outbreaks of "dancing mania"—mass psychogenic events where hundreds of people would dance uncontrollably for days, claiming they couldn't stop.

The Church's response to these events was positively schizophrenic. Sometimes, they treated it as demonic possession requiring exorcism. Others, as divine ecstasy requiring pilgrimage. And the dancers themselves often reported religious visions, feeling compelled by saints or angels.

Were these early forms of charismatic worship? Or were they simply mass hysteria? Perhaps ergotism from contaminated grain? The contemporary accounts don't give us enough to definitively say, but what is clear is that these events terrified authorities, precisely because they represented uncontrolled religious experience.

And by now, you should already know how much that freaked out the Church!

Later, in 17th-century England, the Ranters took religious antinomianism to its logical extreme: if salvation freed you from the law, they reasoned, then nothing you did could be sinful.

They reportedly engaged in blasphemy and all flavors of sexual promiscuity, all while claiming divine inspiration. The Commonwealth government suppressed them brutally, partly because of their behavior, but primarily because their theology undermined all social order.

After all, if God's grace made all actions equally holy, then what was the point of church, state, or any authority at all?

On the opposite end of this spectrum, we’ve got the Medieval Cathars and their "perfecti," who represented a more structured approach to holy madness.

These spiritual elites practiced such extreme asceticism that they often appeared mad to outsiders: starving themselves, refusing to touch money or own property, and welcoming death as liberation from the material world. Yet, they were revered as living saints by Cathar communities.

The Catholic Church found them so threatening that it launched the Albigensian Crusade, one of the bloodiest religious wars in European history, specifically to exterminate them.

More on the Cathars later.

Anyway, in today’s day and age, modern psychiatry has medicalized religious madness, creating categories like "Jerusalem Syndrome" for tourists who develop messianic delusions in the Holy Land. Yet the relationship between mental illness and religious experience remains complex.

Many mystics throughout history likely suffered from what we'd now diagnose as temporal lobe epilepsy, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Does that invalidate their spiritual experiences? The question itself reveals our discomfort with the possibility that madness and divinity might not be opposites, but overlapping territories.

The Frenzied Flame in Elden Ring taps into this ancient anxiety: what if the madmen are right? What if conventional sanity is actually a delusion, and only those broken enough to see past their own conditioning can perceive cosmic truth?

It's a question that religions have grappled with forever, usually by elevating certain forms of divine madness while suppressing others. Which brings us back, once again, to this Volume’s main theme: the difference between mystic and madman—like the difference between prophet and heretic—often comes down to nothing more than institutional endorsement.

The Blasphemous Serpent and the Revolution That Devours Itself

"Join the Serpent King, as family. Togethaaaa, we will devour the very gods!"

~Rykard, Lord of Blasphemy

Whereas the Frenzied Flame wants to burn everything back to primordial unity, Rykard, Lord of Blasphemy, wants to eat his way to godhood—literally.

His transformation into the God-Devouring Serpent might well be the most gratuitously disgusting heresy in Elden Ring, but it also serves as a particularly… *ahem*… biting metaphor for an all-too-familiar phenomenon in our world: revolutionary violence that becomes so all-consuming it devours even the revolutionary.

It's the logical endpoint of "eat the rich," taken to cosmic extremes: why stop at the aristocracy when you can devour the gods themselves?

Rykard starts as one of the more politically sophisticated characters in Elden Ring's backstory. A praetor (military magistrate) of the Golden Order who becomes disillusioned with its reign (as one does), he doesn't just rebel: he organizes.

The Recusants of Volcano Manor aren't random heretics. They’re a structured revolutionary movement with clear goals:

Hunt down champions of the Erdtree,

Destabilize the Golden Order through targeted assassinations,

ProfitUltimately overthrow the gods themselves.

Rykard’s Recusants practice guerrilla warfare with a theological bent—each murdered Tarnished is one less potential Elden Lord to restore the old order.

But Rykard's story soon becomes a cautionary tale about revolutionary excess. Faced with the overwhelming might of the Golden Order, he makes the ultimate sacrifice… or rather, what he thinks is sacrifice: he feeds himself to the God-Devouring Serpent, an ancient being that existed long before the Erdtree, gaining its power to devour and absorb anything, even gods.

His transformation is quite grotesque, even by Miyazaki and GRRM’s standards: Rykard's face emerges from the serpent's mouth like a parasitic growth, still speaking, and still conscious, but no longer entirely human, or entirely himself.

The serpent promises the power to consume the very gods ("togethaaaa we will devour the very godssss," as Rykard famously hisses in one of the game's most memorable boss encounters). But it doesn’t take long before consumption becomes compulsion.

And so, the revolutionary who sought to free the world from the yoke of divine tyranny becomes a tyrant himself, demanding his followers feed him champions to grow ever stronger.

The Volcano Manor, once a haven for noble rebels, becomes a cult of personality centered on an ever-hungry god-snake that might be even worse than what it sought to replace. Just ask the caged and shackled Albinaurics strewn about the Manor’s torture chambers what they think of Rykard’s new order.

And Mt. Gelmir, the Mordor-like region that houses the Volcano Manor, would become the site of the most grotesque and hellish battles of the Shattering, a literal meat grinder of a stalemate that left mountains of corpses strewn across a scorched, barren wasteland.

Rykard’s degeneracy is tragic because he was right about the problem. The Golden Order is tyrannical, and its gods are parasites. Hell, the Erdtree itself feeds on the souls of the dead! His diagnosis was accurate, but his cure became worse than the disease. In trying to gain enough power to challenge the gods, he became something that made even the gods look reasonable by comparison.

In short: the revolutionary became the revolution, and the revolution became an all-consuming maw that existed only to feed itself.

The Recusants who still serve him show various levels of awareness about what their lord has become. Tanith, his consort, remains devoted to the point of literally eating his corpse after you defeat him, hoping to carry on his essence. Patches, ever the pragmatist, seems to work with Volcano Manor purely for profit while maintaining healthy skepticism about its goals. Bernahl, perhaps the most clear-eyed, morosely walks the path of his own damnation with a self-awareness that’s paradoxically (almost) honorable.

But none ultimately stand up to Rykard, even though it’s long been clear that the serpent has become an existential threat to everyone, including its own followers. They continue following him down the road to hell, because the few that made the mistake of challenging him early on suffered fates far worse than death.

🐍😋♾️ SIDE QUEST: Eating God for Dummies

The serpent occupies a unique position in religious symbolism: simultaneously the wisest and most cursed of creatures, it is both the bringer of knowledge and the source of damnation.

That Rykard chose fusion with a serpent to challenge divine authority is no accident: he's following a tradition of serpentine rebellion that predates Christianity, and persists despite millennia of suppression.

In Gnosticism, particularly among the Ophites (literally "serpent people"), the serpent of Eden wasn't Satan, but humanity's liberator. In their reading, the Old Testament God was the real villain, a false demiurge who created the material world as a prison and wanted to keep humans ignorant and enslaved.

The serpent, by offering knowledge, was therefore trying to free humanity from cosmic tyranny. The Ophites actually venerated the serpent in their ceremonies, seeing it as a manifestation of divine wisdom (Sophia) trying to enlighten humanity despite the demiurge's opposition.

This is a complete inversion of orthodox6 theology, which naturally made it intolerable to mainstream Christianity. The Ophites were declaring that everything the Church taught was not just wrong, but backwards—God was evil, the serpent was good, and the Fall was actually an ascent toward knowledge.

Church fathers like Irenaeus wrote extensive polemics against them, because their theology was more than just heretical (that in itself would’ve been bad enough)—it threatened the entire moral framework of mainstream Christianity.

After all, if the serpent was right to offer forbidden knowledge, then maybe all forbidden knowledge should be pursued. And if God could be a tyrant, then maybe divine authority should be questioned.

Obviously, this could not stand. And so, the early and Medieval Church snuffed out Gnostic thought with vigor and gusto, as we’ve convered back in Part 1.

Meanwhile, the ouroboros—the serpent eating its own tail—appears in alchemical and hermetic traditions as a symbol of eternal cycles, self-sufficiency, and the prima materia that contains all things within itself.

But there's a darker reading that Rykard embodies: the revolution that consumes itself, the appetite that can never be satisfied, and the power that exists only to perpetuate its own expansion. The ouroboros promises completeness, but instead delivers endless consumption.

Revolutionary movements have always struggled with the symbolism and reality of this consumption. The language of revolution is full of digestive metaphors—eat the rich, devour the aristocrats, consume the old order.

During the French Revolution's Terror, this wasn't entirely metaphorical! There are documented cases of revolutionary crowds literally consuming parts of their enemies—eating hearts, drinking blood, and parading flesh on pikes.

The revolution that promises to devour the old order risks becoming addicted to devouring, as an end in itself, unable to stop consuming even when it runs out of enemies and starts eating its own.

Saturn Devouring His Son, Francisco Goya's famous painting, perfectly captures this self-consumptive horror: the god who eats his children to prevent them from overthrowing him becomes the revolution that eats its own to preserve its purity.

Robespierre sends Danton to the guillotine, Stalin purges the old Bolsheviks, and the revolution eventually runs out of external enemies and inevitably turns inward. What starts as righteous anger against oppression invariably becomes an endless appetite for ideological purity that can never be satisfied.

This theme appears elsewhere, as well.

Take the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, who provides another parallel. In some versions of the myth, he was tricked into consuming human flesh and blood (or, in other versions, into drunkenness and incest), breaking his own taboos and forcing his exile. This is the god who transgresses his own boundaries and consumes what should not be consumed, losing his divinity and thus fleeing in shame. Yet he promises to return, to reclaim his power—the eternal cycle of the revolutionary who becomes corrupt, falls, and dreams of return.

And more recently, in contemporary political movements, we see this consumptive dynamic play out repeatedly. Revolutionary groups constantly splinter and purge, each faction accusing the others of insufficient purity. The movement always eats itself in pursuit of an ever-receding ideal.

The online left's "circular firing squad" phenomenon, where activists destroy each other’s reputations, careers, and social capital over increasingly minor ideological differences, mirrors Rykard's transformation—the fight against tyranny becomes its own form of tyranny, consuming everything in its path, including itself.

Meanwhile, the Church of Satan and other modern Satanist movements have reclaimed the serpent as a symbol of rebellion against arbitrary authority, but even they acknowledge the danger Rykard represents.

The serpent that offers knowledge and liberation can become the serpent that devours everything, including its own tail, its own followers, and its own purpose. The progression from revolutionary consumption of the old order to just consumption for its own sake is predictable and perhaps inevitable, no matter how much revolutionaries refuse to admit it.7

Miquella's Unalloyed Gold and the Haligtree

"My brother will keep his promise. He possesses the wisdom, the allure, of a god – he is the most fearsome Empyrean of all."

~Malenia's Winged Helm (item description)

Now we come to perhaps the most tragic of the alternative orders: Miquella's Haligtree. Here, we see an attempt to create something genuinely better than the Golden Order—more welcoming, more compassionate, more pure.

Yet even this utopian project, born from the best intentions, becomes corrupted into something monstrous. It's a reminder that even benevolent theocracy is still theocracy.

Miquella is fascinating because he starts from a lofty position—born an Empyrean, beloved of the Golden Order, and possessed of supernatural charisma—yet chooses to reject his station to create something new. Reflecting this, his Unalloyed Gold is specifically designed to resist the influence of Outer Gods,8 including the Greater Will itself.

So, Miquella’s not trying to serve a different master; he's trying to create a system free from all external divine interference.

The Haligtree was meant to be a sanctuary for all those rejected by the Golden Order. Misbegotten, Albinaurics, and others who lived outside Grace found welcome there. And his followers didn't worship him out of fear or obligation, but out of genuine love—his supernatural charm made everyone he met want to protect and serve him.

But there's something deeply unsettling about that charm, isn't it? The game never lets us forget that Miquella's compassion comes with coercion. People don't choose to love him; they're compelled to. His kindness is a kind of mind control, his sanctuary a gentle prison.

The Shadow of the Erdtree DLC makes this even more explicit: Miquella's incipient "Age of Compassion" would involve stripping everyone of their free will to ensure they could never choose cruelty.

Indeed, in the DLC, the Tarnished ingratiates himself to a cadre of Miquella’s champions tracing his path through the Land of Shadow. At some point, Miquella’s charming spell breaks, and his fragile coalition quickly fractures due to mutual suspicion, paranoia, and general ill-will amongst a group of ambitious warriors who—without Miquella’s charm forcibly binding them together—actually had little in common with each other, and had sharply divergent and even opposed interests.

And in the DLC, we find out that it actually wasn’t Mohg who kidnapped Miquella—it was the other way around. Miquella charmed Mohg into falling in love with him and “kidnapping” him, so as to gain access to the Land of Shadow.

He was pulling the strings the entire time, using the feared Lord of Blood as nothing more than a pawn, a stepping stone on the path towards ascention to godhood.

Miquella’s new order is the highest expression of benevolent totalitarianism: peace through the complete elimination of choice.

Meanwhile, St. Trina, Miquella's alter ego associated with sleep and dreams, represents another form of escape from suffering: not through destruction like the Frenzied Flame, but eternal slumber. Her followers find peace in unconsciousness, freed from the pain of waking life.

It's a gentler apocalypse, but an apocalypse nonetheless. The choice between Miquella's forced compassion and St. Trina's eternal sleep is really no choice at all. Both represent the abnegation of human agency in favor of externally imposed peace.

Meanwhile, back in the Lands Between, what ultimately happened to the Haligtree in Miquella's absence reveals another fundamental problem with utopian projects built around singular charismatic leaders.

Without Miquella's presence, his sanctuary became a rotting fortress where his followers waited desperately for a return that never came, and never will come. Malenia, driven mad by rot and loss, transformed from protector to destroyer. And the Haligtree itself, meant to rival the Erdtree, now stands withered and dying, bearing somber witness to a dream cut short by the cruelty of reality.

This shows us how even the most benevolent alternative to orthodoxy becomes corrupted without constant vigilance and maintenance.

☀️🏃🏚️ SIDE QUEST: Heaven Can’t Wait (DIY Paradises)

The promise of building Heaven on Earth has motivated some of history's most inspiring religious movements… and justified some of its bloodiest reprisals. When groups claim they've found a better way to achieve salvation, especially one that bypasses established religious authority, the response from orthodox powers is often swift and merciless.

In fact, the history of Christian "heresies" is actually largely a history of heterodox communities that threatened theological doctrine and the entire social order built on that doctrine.

The Cathars of medieval southern France were one of the most successful alternative Christianities in European history. They were theological dissidents, sure, but that vastly undersells the magnitude of their accomplishments: they built a functioning counter-church, complete with its own hierarchy, sacraments, and territorial control.

Their Gnostic theology was radically dualistic. In their view, the material world was created by an evil demiurge, and only through complete rejection of physicality could the soul return to the true God. This was a complete abnegation of the Catholic Church's worldly power, wealth, and claim to mediate salvation through physical sacraments.

On top of that, the Cathar perfecti lived lives of such austere holiness that even the Vatican’s chroniclers begrudgingly admitted their moral superiority to most Catholic clergy. They practiced complete poverty, celibacy, and vegetarianism. They also treated women as spiritual equals, allowing them to become perfecti—unthinkable in the Catholic hierarchy. But most threatening of all, they offered a form of Christianity that needed no churches, no priests, and no tithes—just spiritual commitment and community support.

The Catholic Church responded entirely predictably: with genocide. The Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229 CE) specifically targeted not just Cathar believers, but the entire civilization that harbored them.

The Crusaders burned entire cities, massacred their populations, and destroyed the sophisticated Occitan culture surrounding them. The famous quote "Kill them all, God will know his own" comes from this crusade. And after the dust settled, the Inquisition was literally set up to root out surviving Cathars. By the 14th century, Catharism was extinct—an entire alternative Christianity, completely erased from existence.

Then we have Joachim of Fiore, a 12th-century mystic approved by multiple popes during his lifetime, who inadvertently spawned centuries of theologically revolutionary movements.

His prophecy of the "Age of the Holy Spirit"—a coming era where divine grace would flow directly to believers without the need for church mediation—became the blueprint for countless utopian heresies throughout the centuries that followed his life and death. The Spiritual Franciscans, the Fraticelli, and the Brethren of the Free Spirit all claimed that Joachim's vision justified their rejection of church authority in favor of direct divine inspiration.

The Brethren of the Free Spirit (like the Ranters several centuries later) in particular took antinomianism to its logical conclusion: if you were truly saved, and therefore truly united with God, then nothing you did could be sinful. Sin was therefore just an illusion created by the fallen world.

They allegedly held communal property, practiced sexual freedom, and completely rejected all social hierarchy. Whether they actually did these things, or whether these were just accusations from their enemies, is historically unclear—the Church destroyed them so thoroughly that all we have left are hostile accounts of their beliefs.

But the most successful of these heretical sects were perhaps the Taborites of 15th-century Bohemia, who actually achieved what most utopian heretics have only dreamed of: they actually built their holy community and defended it militarily.

The city of Tábor was organized on proto-communist principles: no private property, no social hierarchy, and all goods shared in common. They believed the Second Coming was imminent, and that they were God's chosen warriors to cleanse the world of corruption. Their military innovations (among them war wagons, early firearms, and combined arms tactics) let them defeat multiple crusades sent against them. It took two decades and the combined might of the Holy Roman Empire to finally crush them.

All these movements shared the belief that the Kingdom of Heaven didn't have to wait for death or the Second Coming—it could be built here and now, through human effort guided by divine inspiration.

Naturally, this was intolerable to established Christianity. But not because it challenged specific doctrines, but rather because it undermined the entire logic of spiritual authority. After all, if Heaven could be achieved on Earth through alternative means, what was the point of the Church to begin with?

And the pattern repeats even in modern times. Take, for example, The People’s Temple (the Jonestown folks), the Branch Davidians, and Heaven's Gate, to name just a few.

Each promised a perfected community that transcended conventional Christianity's limitations. And each ended in tragedy.

The distinction between utopian religious community and destructive cult is often visible only in retrospect, and sometimes not even then.

Scarlet Rot and the Divinity of Decay

"The scarlet bloom flowers once more. You will witness true horror. Now, rot!"

~Malenia, Goddess of Rot

While Miquella's Haligtree withers as a testament to utopia arrested in eternal youth, his twin sister Malenia's Scarlet Rot (which refers to both an Outer God and the blight it spreads through the realm) represents the other side of that coin: corruption that claims divinity through decomposition.

The Rot, on first glance, seems like yet another fantasy metaphor for disease or decay—but it's actually an alternative form of life, a different answer to what existence could be. Where the Erdtree promises eternal golden preservation, and the Frenzied Flame offers purifying destruction, the Scarlet Rot offers transformation through decomposition, beauty through decay, and divinity through disease.

Malenia's relationship with the Rot is the game's most complex exploration of unwanted blessing. She was born cursed with this affliction; she didn't choose to be the vessel for an Outer God's influence.

The Rot is simultaneously her greatest weakness and her ultimate strength. It's killing her slowly, and has already claimed her eyes and limbs (replaced with prosthetics), yet it also makes her one of the most fearsome warriors in the Lands Between.

She's never known defeat in battle until the player comes along—even her fight with Radahn ended in a draw, and only because she chose to unleash the Scarlet Rot's full power, nuking the region of Caelid into a festering wasteland.

What’s really sad about it all is that Malenia never wanted to be the carrier of Rot. She's spent her entire life resisting this apotheosis by using her brother Miquella's Unalloyed Gold needle to keep the Rot at bay, and by defining herself as a blade rather than a plague vector. She is Malenia, Blade of Miquella, not Malenia, Avatar of Rot.

But the game makes it clear this resistance is ultimately futile. In the second phase of her boss battle, she becomes Malenia, Goddess of Rot—whether she wants it or not. The Outer God doesn't need her consent, only her body as a vessel.

The Scarlet Rot’s indiscriminate nature is a large part of what makes it horrifying as a divine force. It doesn't convert followers or demand worship—it just spreads.

The Kindred of Rot, those prawn-like beings fully transformed by its influence, aren't evangelists, but vectors. They don't preach; they simply exist as walking demonstrations that decay is just another form of life.

And the massive Rot flowers that bloom across Caelid aren't trying to convince anyone of anything. They're just doing what life does: growing, spreading, and transforming everything they touch into more of themselves.

Caelid itself stands as a monument to what divine rot looks like at scale. Once a verdant region, it's now a hellscape of red decay where the sky burns crimson and dogs grow to the size of houses.

Yet, it's not dead—if anything, it's too alive, teeming with mutated life that shouldn't exist but does. The Rot doesn't kill so much as transform, creating new forms of existence that are completely alien to conventional life, but equally valid in their own grotesque way. It's evolution through corruption, or speciation through sickness.

And the Lake of Rot—the seeming origin of the Rot, festering deep beneath the earth like a putrid open sore—suggests that the Scarlet Rot predates the current order by eons. So this isn't some new heresy, but an ancient alternative to conventional existence. It’s older than the Erdtree, older than the Golden Order, and possibly older than complex life as we understand it.

The God of Rot isn't trying to conquer or convert. It's simply waiting for everything else to decay into its domain. Everyone knows that given enough time, everything rots. The Scarlet Rot just accelerates the process.

There's something almost refreshingly honest and oddly beautiful about this form of divine corruption. Unlike the Golden Order's false promises of eternal preservation, or Miquella's forced compassion, the Rot makes no claims about improvement or salvation. It simply is what it is: decay, transformation, and the inevitable end of all things that pretend to permanence.

In a world full of brutal gods and warring demigods making grandiose empty promises but only delivering misery and strife, the Rot's promise is refreshingly simple: everything ends, everything changes, nothing lasts forever, and that's not just okay—it's godly.

🤢🧟♂️🌸 SIDE QUEST: To Decay Is Divine

Decay has always held a paradoxical position in religious thought: the enemy of divine perfection, while simultaneously the necessary prerequisite for resurrection. The horror of decomposition battles with its ecological necessity, creating theological tensions that no religion has fully resolved.

The body that rots is fallen flesh returning to dust, but it's also the seed that must die to bring forth new life. This contradiction runs through Western religion like a fissure, creating spaces where decay itself becomes sacred.

Medieval Christianity's relationship with holy corpses perfectly illustrates this tension. Saints' bodies that didn't decay were considered miraculous, proving divine favor through incorruptibility. Yet at the same time, the Church treasured relics that were often fragments of very decayed bodies—think finger bones, dried blood, and other pieces of rotted flesh.

Oh, and lest we forget: the same tradition that saw corruption as evidence of sin also practiced ritual cannibalism through transubstantiation, and venerated body parts as sources of divine power. The corpse was simultaneously sacred and profane, corrupt and incorruptible.

Leprosy in medieval Europe, meanwhile, functioned as living decay, as corruption made flesh while the flesh still lived. And the Church's response was… a tad confused.

On one hand, it considered lepers as cursed by God, punished them for sin (their own or their parents'), excluded them from society, and forced them to carry bells warning of their approach.

But simultaneously, it saw them as "Christ's poor," especially beloved by God, and considered their suffering a form of purgatory on earth that guaranteed salvation upon death. Leper hospitals were religious institutions, and considered those who cared for lepers as especially pious. Some saints even deliberately exposed themselves to leprosy as a form of mortification.

St. Francis kissed lepers as more than an act of charity—in doing so, he recognized and acknowledged that in decay lay divinity. The corrupted flesh of the leper was closer to Christ's suffering than healthy flesh could ever be, and the boundary between sacred and profane dissolved in the reality of decomposition.

Some medieval mystics went even further, drinking the pus from lepers' sores or eating their scabs as forms of extreme devotion, finding God in putrefaction itself.

The tradition of the danse macabre, in turn, acknowledged decay's universality as a form of democracy. Kings and peasants, saints and sinners, all ended up as skeletons dancing together. No matter their station in life, everyone had to face the reaper one day. Death and decay were thus the great equalizers that revealed the pretensions of earthly hierarchy.

Similarly, the memento mori—”remember, you must die”—was partly about humility, sure, but more than that, it was a recognition of decomposition as the truth beneath all temporary human achievement. Your body is already dying and decaying; enlightenment means accepting this rather than denying it.

Eastern traditions, by contrast, often embrace decay more directly. The Buddhist practice of corpse meditation (maranasati) involves contemplating bodies in various stages of decomposition to understand impermanence.

Meanwhile, Tibetan sky burial offers corpses to vultures, acknowledging that the body's final act of generosity is to become food for other life.

And finally, the Aghori sadhus of India deliberately court pollution, meditating in cremation grounds, wearing human bones, and even engaging in ritual necrophagy, finding spiritual power in what others find wholly corrupting.

Today, contemporary ecology has resacralized decomposition through the lens of nutrient cycles and soil health. Compost thus becomes a spiritual practice, and decomposition a form of communion with the Earth.9 The mycorrhizal networks that connect forests—what some call the "wood wide web"—depend on fungal decomposers that break down dead matter to feed the living.

Without rot, there is no forest. Without decay, there is no life. The composters of decomposition are therefore performing a sacred function more essential than any human priest.

And let’s not forgot how the COVID-19 pandemic forced a global confrontation with invisible corruption: deadly disease that spread through breath, surfaces, and proximity to one another. During those harrowing years, the asymptomatic carrier became a figure of horror—corrupted and corrupting without even knowing it, spreading decay while appearing healthy.

Malenia, who carries the Scarlet Rot while maintaining her sense of self, embodies this same anxiety about infected identity: are you yourself, or are you the disease? Is there even a difference?

Finally, modern cancer treatment involves controlled putrefaction—chemotherapy that kills faster-growing cells, radiation that damages DNA, and targeted therapies that cause tumors to necrotize from within.

In treating cancer, the oncologist fights corruption with corruption, poison with poison, and death with death. The cancer patient's body becomes a battlefield where different forms of decay compete, where healing looks identical to harming, and where the cure might be worse than the disease but we pursue it anyway because the alternative is unthinkable.

The Dragon Communion Heretics

“Consume a dragon's heart at the altar to make its power yours.

While a terrible and savage-looking thing, the heart has a peculiar beauty to it.”

~Dragon Heart (item description)

Unlike the other entries in this article, Dragon Communion represents a different kind of heresy altogether—not ideological, but practical. These practitioners aren't seeking alternative salvation or cosmic truth. Rather, they're individuals willing to trade their humanity for power, one dragon heart at a time.

It's perhaps the purest expression of spiritual pragmatism in the game. Forget about whose god is real or which order is legitimate—just give me the strength to survive another day.

The Church of Dragon Communion operates on simple principles:

Kill a dragon,

Eat its heart,

Gain its power.

Rinse, lather, repeat.

In return for consummating this dastardly act, the practitioner is granted immense power. Each heart consumed grants access to dragon incantations—breathing fire, roaring frost, sprouting wings... sounds pretty awesome, doesn’t it?

And I’ll grant you that—it absolutely is. Dragon incantations like Dragonfire and Dragonclaw call on the spirits of the dragons whose hearts you’ve chowed down to mete out some seriously overpowered draconic whoop-ass on your enemies.

But there's a cost to Dragon Communion that goes beyond just the moral squick of dragon-slaying (recall that dragons in Elden Ring are sentient beings of higher order, and linked to the Greater Will itself).

If you consume too many hearts, and rely too heavily on draconic power, you begin to transform. Your head elongates, your skin turns to scales, and your mind fades into bestial hunger. The end state of Dragon Communion is the complete loss of human identity—you become a wyrm, crawling on your belly whilst retaining just enough awareness to know what you've lost.

This is fundamentally different from the Ancient Dragon Cult we discussed in Part 1.

Whereas the Ancient Dragon Cult seeks communion with dragons through worship and imitation—thus gaining power through reverence—Dragon Communion is about consumption and domination. You don't pray to dragons; you devour them. And you don't become like a dragon through spiritual transformation; you literally transform into a dragon10 through cannibalistic ritual.

The game presents this as perhaps the most honest of all its myriad heresies. There's no pretense of higher purpose, nor claims of divine mandate. The Dragon Communion practitioner knows exactly what he’s doing: trading humanity for power. The transformation isn't a surprise or a trick—it's the explicit end point of the path.

Every dragon heart consumed is a conscious step toward inhumanity.

As usual, what makes this subversive in the context of the Lands Between is how it bypasses all the usual power structures. You don't need the Golden Order's grace, the Academy's education, or an Outer God's favor. You just need the strength, skill, and lack of moral gumption to kill a dragon.

It's meritocracy in its most brutal form—power goes to whoever can take it, regardless of birth, blessing, or belief. In a realm where might very much makes right, this is perhaps the most straightforward expression of the Lands Between’s most fundamental dynamics.

🐺🔛🧙♂️ SIDE QUEST: Furry Theology

The fear of human transformation into something inhuman runs deep in the Western religious tradition. Oh, so deep.

The ability to change shape—and in doing so, to violate the boundary between human and animal, and between self and other—represents one of the most profound transgressions of divine order. God made humans in his image; to willfully alter that image is to reject God's plan itself.

Medieval Europe's werewolf trials, often overlooked in favor of the more famous witch trials, reveal how seriously Christian authorities took the threat of transformation.

Between the 15th and 17th centuries, hundreds were executed for lycanthropy. The theological authorities didn’t debate whether werewolves existed—that was taken as given—but whether the transformation was physical or spiritual.

In other words: could Satan actually change human flesh, or did he just create illusions? The implications were enormous: if the Devil could physically transform God's creation, what did that say about divine sovereignty?

And they were kinda pressed for answers, considering the Germanic and Norse peoples that Christianity sought to convert had rich and longstanding shapeshifting traditions.

Take, for instance, the Berserkers who wore bear and wolf skins while entering battle trances where they believed they became the animals whose pelts they wore.

Whether this transformation was psychological, pharmacological (possibly involving psychoactive mushrooms), or purely ritualistic, it represented a spiritual technology that Christianity couldn't incorporate—and therefore had to destroy. The Church suppressed berserker cults both to end a pagan practice, and to establish the human form as fixed, God-given, and inviolable.

Meanwhile, the witch trials' obsession with familiars—animals that were supposedly witches in disguise or spirits (usually demons) in animal form—reflected the Church’s deep anxiety about categorical boundaries.

The witch's familiar violated the taxonomy of creation by being neither fully animal nor fully demon, and by existing in a liminal space that threatened ordered reality. Thus, the accusation that witches could transform into cats, rabbits, or birds touched on the fundamental instability of selfhood itself.

Indigenous shamanic traditions worldwide have also maintained similar types of human-animal transformation as core spiritual practice, and their suppression by Christian authorities followed predictable patterns.

Whether Siberian shamans becoming reindeer, Amazonian and Mesoamerican shamans becoming jaguars, or Native American skinwalkers, Christian missionaries saw the ability to transcend human form as explicitly Satanic.

Thus, while the systematic destruction of these practices wasn’t exactly appreciated by native populations, from the Church’s perspective this was a theological necessity, because a worldview where the human form is sacred and fixed cannot coexist with one where shapeshifting is possible, let alone beneficial.

And the theological horror of transformation transcends mere boundary violations.

In Christian metaphysics, the human form is teleologically oriented toward resurrection. On Judgment Day, the dead will rise in perfected versions of their earthly bodies. But what happens to someone who died as a wolf? What body does a shapeshifter get resurrected into? These aren't trivial questions! Indeed, they strike at the very heart of Christian eschatology and the promise of eternal life.

Recently, contemporary chaos magic and some forms of neo-shamanism have reclaimed shapeshifting as a practice, though usually in purely psychological or astral terms rather than literal physical transformation.

At the end of the day, the idea that consciousness can adopt different forms represents a fundamental challenge to Western religious and philosophical traditions that assume a fixed and singular self. Even when practiced purely as visualization or ritual theater, shapeshifting magic insists that the boundaries of self are negotiable, and that human form is a starting point rather than a fixed destination.

Ranni's Lunar Conspiracy

"Here beginneth the chill night that encompasses all, reaching the great beyond. Into fear, doubt, and loneliness... As the path stretcheth into darkness."

~Ranni the Witch (emphasis mine)

Finally, we come to the realm’s most successful heresy: Ranni the Witch's conspiracy to kill the Golden Order's one true god and replace it with the uncertain darkness of the moon and stars.

Ranni, quite the overachiever, works towards goals that go beyond reform and alternative power: she wants to fundamentally restructure how divinity interacts with the world.

Her “Age of Stars” ending doesn't establish a new order so much as it removes order itself from immediate human experience, placing it at such vast remove that people must figure things out for themselves.

Ranni's rebellion begins with the ultimate blasphemy: deicide. She orchestrates the Night of the Black Knives, stealing the Rune of Death and using it to kill her own Empyrean flesh and Godwyn's soul simultaneously.

This isn’t a regular ole’ murder—it's a metaphysical strike at the Golden Order's most fundamental assumptions. Destined Death, which Queen Marika had removed from the Lands Between to create her deathless order, returns here as a weapon against that very order.

But the witch’s true chutzpah lies not in her methods, but in her vision. She doesn't want to become a god herself, despite being an Empyrean capable of doing so: she wants to remove godhood from the equation entirely.

Ranni’s Age of Stars would take divine order (physically represented by herself as the new god and the Tarnished as her consort and Elden Lord) and place it so far from the world that its influence becomes invisible. People would live and die without certainty of divine will, forced to create meaning and morality for themselves.

The moon that Ranni serves really drives home this symbolism. It isn't really a counter-god to the Greater Will, but rather the absence of god: the cold light that illuminates but doesn't warm, and marks time but doesn't judge. Where the Golden Order offers absolute truth, and the various Outer Gods offer various alternative absolutes, Ranni offers cosmic uncertainty as a form of freedom.

Her order is disorder, her truth is doubt, and her gift is the terror and possibility of genuine choice.

And part of what makes Ranni's ending so compelling is how the game presents it as potentially the best outcome despite (or perhaps because of) its uncertainty. The Tarnished who chooses her path doesn't get to rule the Lands Between in any meaningful sense. He leaves with Ranni on a thousand-year journey through the stars, abandoning the world to figure itself out.

It's an abdication disguised as victory, a rejection of power presented as its ultimate achievement.

🌕🔭🤷🏼♀️ SIDE QUEST: No God’s Sky

The cosmic uncertainty that Ranni offers—a world where divine will becomes invisible and unknowable, and where people must navigate through reason rather than revelation—mirrors one of Christianity's greatest historical defeats: losing ownership of the cosmos itself to science.

For over a millennium, the Church controlled moral, spiritual, and even physical truth. The structure of the heavens, the movement of the stars, and the very architecture of reality were all theological questions, with theological answers provided by the scriptures and their clerical interpreters.

Then came the telescopes, mathematics, and empirical observations that revealed a universe far stranger and more vast than any scripture had imagined.

The parallels between Ranni's lunar order and the Scientific Revolution run deep. Both replace comfortable certainty with uncomfortable truth, divine proximity with cosmic distance, and the promise of salvation with the burden of self-determination.

When Galileo pointed his telescope at the moon and saw not a perfect heavenly sphere but a cratered, mountainous world like our own, he made more than an astronomical observation—he committed theological heresy.

The heavens were supposed to be perfect and incorruptible—fundamentally different from our fallen Earth. Seeing the moon's imperfections was like seeing God's fingerprints smudged.

The Church, in panic, tried everything it could to deal with this nascent cosmological revolution.

They tried suppression—Galileo's house arrest, Bruno's burning, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum banning heliocentric texts.

They tried incorporation—Jesuit astronomers becoming some of the best in Europe, trying to reconcile observation with doctrine.

And they tried reinterpretation—suddenly all those Biblical passages about the sun standing still or the Earth's fixed foundations becoming metaphorical rather than literal.

Nothing worked.

Once people could see Jupiter's moons orbiting something other than Earth, the entire edifice of divinely ordered cosmology began to crumble.

Then, the Enlightenment philosophers who followed the Scientific Revolution took it a step further, challenging the very idea that divine revelation was necessary for understanding reality.

Immanuel Kant's "Sapere aude!" (“dare to know”) encouraged intellectual courage, declaring independence from theological authority. After all, if reason could unlock the laws of physics, why not the laws of ethics as well? Furthermore, if observation could reveal cosmic truth, why did we even need revelation to begin with?

These philosophers weren't all atheists, but their deism relegated God to a cosmic clockmaker who wound up the universe and walked away: distant, uninvolved, and essentially irrelevant to daily life.

This is exactly what Ranni proposes: a god so distant as to be functionally absent. Her thousand-year journey into the stars—as part of her new order—ensures that divine will, while perhaps still existing, becomes utterly removed from human experience.

People in the Lands Between would have to create their own meaning, establish their own morality, and build their own societies without either the comfort of divine guidance or the threat of divine punishment.

It's not true atheism—the order, after all, still exists—but it's functional atheism, where divine absence becomes indistinguishable from divine non-existence.

And the social implications of the IRL Enlightenment's cosmic revolution mirror what Ranni's age would bring: when the Church lost its monopoly on cosmic truth, it began losing its monopoly on earthly power.

It’s hard to imagine how it could not—after all, if priests could be wrong about the heavens, why trust them about governance? If scripture misunderstood the solar system, why believe what it says about social systems?

The divine right of kings, the Great Chain of Being, and the entire hierarchical structure justified by cosmic order (just to name a few)—all became negotiable once the cosmos itself became a matter of scientific rather than theological inquiry.

Consider the profound loneliness of the Enlightenment worldview, which Ranni explicitly embraces.

Medieval Christians lived in a cosmos where everything had meaning, purpose, and divine intention. Every star was placed deliberately. Every event had providential significance. Every human soul was known and valued by an omniscient God.

By contrast, the scientific cosmos revealed by Newton and Galileo was vast, cold, and utterly indifferent to human vagaries. Pascal's terror at the "eternal silence of infinite spaces" captures the existential vertigo of realizing you live in a universe that doesn't care about you.

Meanwhile, in the Lands Between, Ranni's "fear, doubt, and loneliness" isn't a curse, but an accurate description of conscious existence in a universe without accessible divine meaning.

Yet the Enlightenment also argued this cosmic loneliness was the price of human dignity.

Kant's categorical imperative, along with Rousseau's social contract and Voltaire's religious tolerance, all assumed humans could create moral systems without divine command.

The American Revolution's "self-evident truths" claimed to derive from reason and nature, not scripture.

And the French Revolution went furthest of all, attempting to create an entirely new calendar, new religions of Reason, and new social orders based on rational principles rather than traditional authority (they failed spectacularly in many ways, but the genie was out of the bottle: human reason had declared independence from divine revelation11).

The Church never fully recovered from losing the cosmos. It retreated from claims about physical reality, ceding science to scientists while trying to maintain authority over spiritual and moral truth.

But once you've admitted being catastrophically wrong about whether the Earth moves, your claims to infallibility in other matters start to ring hollow. Indeed, the modern Church's careful dance around scientific topics (like accepting evolution but insisting on divine guidance, or acknowledging cosmology but maintaining the special creation of souls) reveals an institution that’s long since learned that it can't win fights against telescopes and fossils.

And that, more than anything, is the world Ranni offers: not one where the gods are dead (sorry, Nietzche), but where they're absent; not where meaning doesn't exist, but where it must be created in a cosmos that isn’t necessarily hostile, but rather indifferent.

It's the Enlightenment bargain: trade certainty for freedom, comfort for dignity, and divine presence for human agency.

And just like the Enlightenment, it's presented not as a loss but as liberation. It’s not abandonment, but maturation; though it may read as divine rejection, it’s more humanity finally being trusted to find its own way in the dark.

But here's the thing about cosmic loneliness and rational freedom: turns out people don't actually like them very much.

After three centuries of Enlightenment victory laps, we're seeing something unexpected: the kids want their gods back. Not necessarily the old gods in their old forms, but something—ANYTHING—to fill the meaning-shaped hole that pure rationalism left behind.

Young people (especially Gen Z’ers and Younger Millennials) who've never known anything but secular liberalism are converting in droves to Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Islam—and the more traditional and demanding the creed, the better.

They're turning their backs on the comfortable, therapeutic deism their parents settled for, in favor of its polar opposite. They want the full medieval package—mysticism, miracles, absolute truth, and cosmic significance. wrapped up in strictures and scripture.

The very things the Enlightenment promised to free us from have now become religion’s biggest selling points. Structure? Rules? Dogma? Sign us up!

It’d be easy to dismiss this recent religious revival as mere nostalgia or reaction, but I’d caution against writing it off wholesale; this increasingly feels like a verdict on whether people can actually thrive in Ranni's cosmos of cold stars and self-determination.

After all, the secular West gave us everything the philosophers promised—individual freedom, material prosperity, scientific miracles, rational governance—and somehow produced the most anxious, depressed, and lonely generations in recorded history.

Maybe Nietzsche was wrong about God being dead; maybe He was just taking a cigarette break while humanity learned what His absence actually costs.

The irony would be delicious if it weren't so tragic: we spent centuries fighting for the right to create our own meaning, only to discover that DIY existentialism is exhausting, and most people would rather have their meaning pre-fabricated, even if (especially if!) it comes with rules and restrictions.

Ranni's Age of Stars might be the most honest ending in Elden Ring, but honesty, it turns out, is overrated when you're floating alone on a rock hurtling through an indifferent cosmos, desperately refreshing social media at 3 AM, searching for something—ANYTHING—that feels like it matters.

Will Ranni and the Tarnished return to the Lands Between after their thousand-year journey to find a similar situation unfolding? Only time—and perhaps a distant sequel—will tell.

The Eternal Cycle of Power

“Heresy is not native to the world; it is but a contrivance. All things can be conjoined."

~Miriel, Pastor of Vows

"Every church is orthodox to itself; to others, erroneous or heretical."

~John Locke, “A Letter Concerning Toleration” (1689)

Across all these heretical factions, we see a fundamental truth about religious authority: orthodoxy always creates its own opposition. Every boundary the Golden Order draws, and every practice it forbids, becomes a potential source of heresy and alternative power. The Outer Gods don't have to recruit followers—the Golden Order creates them through its own rigidity and dogmatism.

Mohg turns to blood because grace was denied to him from birth, and the merchants summon the Frenzied Flame because they were buried alive for basically no reason.

Miquella creates the Haligtree because his sister's rot can't be cured by “approved” means, while Dragon Communers eat hearts because they need power now, not after a lifetime of proper devotion.

All the while, Ranni orchestrates a divine assassination and yeets the whole structure into the cosmic void because she sees no reforming a system built on fundamental lies.

Each heresy constitutes a different response to religious tyranny: violent revolution, nihilistic destruction, utopian separation, pragmatic transformation, systematic deconstruction... they encompass a wide spectrum of methods, morality, and results.

Yet none are presented as unambiguously good. Even Ranni's liberation comes at a terrible cost and carries an uncertain outcome. Still, neither are they simply evil. They're logical responses to an illogical system, heresies born from orthodoxy's own failures.

The Lands Between stands as a mirror to our own world's religious conflicts, where every claim to divine truth creates its own counterclaims. Every orthodoxy spawns its own heresies, and power determines legitimacy only until legitimacy can no longer maintain power.

Thus, the Outer Gods aren't alien invaders, but the inevitable consequences of an institution that’s created a universe of lies by declaring itself the sole source of truth. When you monopolize salvation, you manufacture damnation. And when you claim divine right, you inspire divine rebellion.

In our next and final installment of this series, we'll examine the role of the player, as the Tarnished, in this cosmic conflict, and his/her role in either upholding or upending the Golden Order’s metaphysical reign. Until then, I beseech thee safe travels, Tarnished, and may thine path be forever guided by the Grace of Gold.

~Jay

Food for Talk: Discussion Prompts

While you wait for the next issue, I invite you to mull over the following discussion prompts. Please reply to this email with your answers, or post them in the comments—I'd love to hear your thoughts!

Which faction would you choose if you lived in the Lands Between?

Would you submit to the Golden Order’s promise of eventual grace?

Would you seek forbidden knowledge, despite the cost?

Would you embrace an Outer God’s alien certainty?

Or would you, like Ranni, try to free the world from gods altogether—even knowing that freedom might be its own kind of tyranny?

Further Reading

The Elden Ring Wiki at Fextralife — An unparalleled resource for any Tarnished who wishes to dive into the game, whether to look up lore or weapon/build stats. — Link

The ENTIRE Lore of Elden Ring (videos) by SmoughTown — This YouTube channel is jam-packed with thorough, well-researched, and thoughtful lore explanation and theory videos. If you really want to dive deep into the lore, this 36-hour long series will bring you fully up to speed! — Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Bonus (Shadow of the Erdtree) | Now Available in Book Form!