Issue 4.4: Games that Go "Bump" in the Night (Part 2)

*Another* Brief & Horrifying History of Horror Games [Part of Game & Word's First Spooooktacular Halloween Special!]

Game & Word Special: Halloween 2022, Part 2

Publisher: Jay Rooney

Author, Graphics, Research: Jay Rooney

Logo: Jarnest Media

Founding Members:

Le_Takas, from Luzern, Switzerland (Member since April 14, 2022)

Ela F., from San Diego, CA (Member since April 24, 2022)

Alexi F., from Chicago, IL (Member since May 13, 2022)

Elvira O., from Mexico City, Mexico (Member since May 18, 2022)

Special Thanks:

YOU, for reading this issue.

Table of Contents

Summary & Housekeeping

Feature: “Another Brief & Horrifying History of Horror Games” (~35 minute read)

Food for Talk: Discussion Prompts

Further Reading

Game & Word-of-Mouth

Footnotes

Summary:

Today, we’ll conclude our chronology of video game horror, examining its evolution from the turn of the millennium to the present day. We’ll also set the stage for next week’s Halloween bonanza!

Housekeeping:

Boo!

Welcome back, everyone! Nothing much to announce here, just a few quick reminders:

Give Us a “Like” and a “Share”

If you enjoy reading Game & Word, the easiest way to support my work is by clicking the “like” button on the top of the article, and sharing this post on social media. It really goes a long way towards improving the newsletter’s discoverability. Thank you most kindly!

Early Issue Next Week

Just a friendly reminder that next week’s issue will be published on Friday, October 28, instead of Sunday, October 30. Be on the lookout!

Previous Issues

NOTE: Game & Word is a reader-supported publication. The two most recent issues are available to all, free of charge, until new issues are published (podcasts and videos will always remain free).

Older issues are archived and only accessible to paid subscribers. To access articles from the Game & Word archive, support my work, and keep this newsletter free and available to all, upgrade your subscription today:

Volume 1 (The Name of the Game): Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Issue 4

Volume 2 (Yo Ho Ho, It’s a Gamer’s Life for Me): Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Bonus 1 ● Issue 4 ● Issue 5 ● Issue 6 ● Issue 7 ● Bonus 2 ● Issue 8 ● Bonus 3

Volume 3 (Game Over Matter): Intro ● Issue 1 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3 ● Podcast 1 ● Issue 4 ● Video Podcast 1 ● Bonus 1 ● Issue 5 ● Podcast 2 ● Issue 6 ● Issue 7 ● Issue 8 ● Issue 9 ● Podcast 3 ● Bonus 2

Volume 4 (Tempus Ludos): Intro ● Issue 1 ● Video Podcast 1 ● Video Podcast 2 ● Issue 2 ● Issue 3

If you’d like to support this publication, but don’t want to commit to a recurring, paid subscription, you can always help offset my caffeine costs by chipping in for a cup of joe:

Feature: Another Brief & Horrifying History of Horror Games

👾🤔🤷 CONFUSED? ➡ NEW GAMING GLOSSARY! 📚💬🧑🎓

Confused by any of the gaming jargon, slang, lingo, or other “insider terminology” on this newsletter? Just click on the term and it’ll take you to its entry on Game & Word’s comprehensive and user-friendly Glossary of Gaming Terms!

🚨🚨🚨 SPOILER ALERT 🚨🚨🚨

This post contains spoilers with varying degrees of spoilerness for Silent Hill, The Last of Us, Yume Nikki, System Shock, BioShock, OMORI, Lamentum, and The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow. You've been warned!

⚠️⚠️⚠️ CONTENT WARNING ⚠️⚠️⚠️

This article contains discussions and visual depictions of horror and everything that comes with it. If you’re easily frightened, disturbed, or upset, please proceed with caution. Portions that are particularly squicky/gruesome will be labeled, but be warned… even the warning labels themselves can be pretty heavy. Reader discretion advised.

⚖️⚖️⚖️ ETHICS DISCLOSURE ⚖️⚖️⚖️

This article contains affiliate links. If you click on any such link and purchase the linked product, Game & Word gets a small cut of the sale. This helps keep the newsletter sustainable without needing to put up paywalls or ads.

A review copy of one of the games featured in this article, The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow, was provided to Game & Word by the publisher. This did not factor whatsoever in my decision to include the game in my coverage, nor did it influence my evaluation of the game.

💡💡💡 POINT OF CLARIFICATION 💡💡💡

Just like last week, this article’s title is “Another Brief History of Horror Games,” which you might have noticed is NOT “Another Complete History of Horror Games.” This article (like the one before it) surveys just a small fraction of the many, many, MANY games that constitute the horror gaming canon. Covering (or even mentioning) every single one would take an entire book, nevermind one issue in one humble newsletter.

So if you’re annoyed I left a game out, it wasn’t intentional. I either missed it, or had my reasons for not including it. If you’d like me to comment on a particular game, though, feel free to drop me a comment or DM letting me know. No promises, but I’ll consider your request.

On a similar note: the categories and subgenres I list here are fluid, and there’s a significant amount of overlap between them. So if you believe I should’ve put Game X into Category Y instead of Category Z, I’ve most likely thought about that already. But you’re probably right. We’re both probably right. At the end of the day, this is just one guy’s opinion.

So, let’s not get hung up on split hairs. Instead, let’s just have fun geeking out and getting spooked over this wonderfully horrifying niche within this wonderfully wonderful hobby we all love and share.

Games Who Fight Monsters: The Horror Genre Mutates & Evolvees (2000s)

“If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

~Friedrich Nietzsche

[CW: mental illness, depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, dissociation]

Silent Hill marked another inflection point in horror gaming’s evolution, but it was so subtle I doubt a lot of players even noticed the shift at the time. On one hand, Silent Hill was undeniably a survivor horror title—in some ways, even more so than the Resident Evil juggernaut that preceded it.

For instance, there was far more of an emphasis on actual survival. The elite police/military/mercenary sharpshooters1 you typically play as in Resident Evil games are clearly battle-hardened and trained for survival situations, which blunts the scare factor somewhat.

This is increasingly pronounced as you near the ends of these games—by then, you’ve cleared out most of the monsters, stockpiled enough ammo to easily take down the rest, and been long desensitized to the once-scary and foreboding atmosphere after hours of jump scares and increasingly predictable chase sequences.

Not so in Silent Hill! The player character, Harry Mason, is just an everyday dude trying to find his missing daughter in a menacing, unfamiliar, and unnatural place, all while trying to avoid similarly menacing, unfamiliar, and unnatural monsters.

Harry’s in way over his head, and it shows. He finds a handgun, but as he’s just an ordinary guy who lacks firearms training, he’s a terrible shot. He’ll rarely hit a target unless it’s at point-blank range, and even then a hit is not guaranteed.

But wait, there’s more! As is befitting this type of game, ammo is highly scarce and needs to be rationed. And just in case that wasn’t enough, gunshots are (surprise, surprise!) LOUD—and so, they tend to alert other nearby baddies, who’ll gladly join in the fun. Harry can barely fend off one monster; a whole gang of them will quickly turn him into corpse chow.

So most of the time, it makes more sense to just repeatedly whack these monstrosities with a crowbar. But that requires getting really up close and personal to these… whatever these things are… and often, it’s too close for comfort.

Fortunately, running away is always an option. And it’s almost always the best option.

And although Harry does become more confident and a better shot as he gets closer to finding his daughter towards the end, he never quite becomes a sharpshooter on the same level as Resident Evil’s Chris Redfield or Jill Valentine.

In addition, Silent Hill avoids the endgame desensitization that neuters survival horror games. How? By constantly pulling the rug from under the player’s feet. I mentioned last week how occasionally, the foggy, snowy, and deserted town of Silent Hill will suddenly transform into a dark nightmare world, with walls made out of bloody rust, chain-link floors standing over a bottomless void, and gruesome monstrosities lurking around every corner.

These sequences are every bit as unsettling as they sound. They’re also spaced out far apart and unpredictably enough that they never lose their frightful charge—not even near the end. Especially not near the end, when the foundation of the bizarre dimension that is Silent Hill starts to crumble, shoving Harry down a Lynchian slide into madness. Everything he2 thought he knew—about himself, his life, and the accursed town he’s trapped in—goes right out the window.

Are you unsettled yet? Now you see why Silent Hill seared itself into the minds of players everywhere. In doing so, it revealed to them a whole new insight—that they could not only get scared by a game, but also disturbed. And even more importantly… they liked it.

Thanks to Silent Hill having codified several psychological horror game genre conventions, players now knew what to look for. And the tidal wave of psych horror games that followed further refined these conventions.

So, what are these genre conventions, anyway? Let us count the ways:

An almost complete absence of truly physical threats, and an increased focus on psychological threats (which are no less dangerous). Most commonly insanity, but can also include trauma (particularly PTSD), dissociation, severe mental illness (especially psychotic disorders like schizophrenia), addiction, or a particularly unpleasant (and often chemically-induced) journey to the darkest recesses of the protagonist’s mind;

A dearth of action-oriented gameplay (a mechanical reflection of the aforementioned psychologically-focused themes). Minimal acrobatics, very little combat, or even no combat at all. If a game does include action, it’s usually limited to the occasional chase, stealth, or escape sequence.

Far more subtlety than zombie/slasher/survival horror—eschews gore-for-shock-value and sudden jump scares to instead create an unsettling and disturbing atmosphere that creates feelings of deep unease in the audience;

The portrayal of the protagonist’s descent into madness by way of making the audience feel mad, often with: bizarre, surreal, and constantly shifting images; nightmarish sensory distortions; blurred lines between lucid and liminal states (ie: dreams, ecstatic trances, psychedelic “trips,” psychotic episodes); and vivid apparitions, hallucinations, or other sights/sounds/smells that may or may not really be there;

Persistent, inescapable, debilitating, oppressive, and intrusive thoughts, fears, traumas, regrets, and insecurities, often leading the protagonist to fall to his knees and cover his hears with his hands, begging the voices in his head to leave him alone;

The protagonist’s almost complete psychological isolation, either from being placed in a mental institution, becoming socially ostracized from a society that’s written him off as a madman, or keeping his suffering to himself for fear of being institutionalized or ostracized;

A lingering doubt in the audience that persists long after the story ends, as to whether or not it was all in the protagonist’s head.

Ever since Silent Hill opened the floodgates, so many developers have described their games as “psychological horror,” regardless of applicability, that it’s become a bit of a buzzword.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The point is, Silent Hill planted a seed in players’ heads. And when survival horror games finally became too big for their britches, instead of a genre implosion, a fork emerged in the road ahead.

The Gaming Dead: The Rise of Indie Horror (Late ‘00s — Late ‘10s)

At some point in the mid to late 2000s, players had a hankering. No, not for brains—but for something new. Zombie-themed, AAA survival horror games were starting to wear out their welcome. With each new derivative zombie shooter, the genre became increasingly played out, and even (most unforgivably) not scary, to the point of easily lending itself to parody.

At the same time, games like Silent Hill and its even more mind-screwy sequel, Silent Hill 2 (2001), had shown the industry that players were ravenously hungry for psychological horror and couldn’t get enough of it. It was undoubtedly some players’ preferred horror subgenre, but for others, it was also something different.3

All of this meant that horror gaming was overdue for some serious innovation. And innovation, it’d get—seemingly out of left field, and then out of right field.

From the left flank, came one game that kept on carrying on the zombie theme, but turned every other zombie game convention on its head. The game was none other than Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead (2012).

From the right flank, came a tidal wave of games that leaned even heavier into the psychological angle. Those that didn’t claim Silent Hill’s pedigree instead traced back to one obscure, free game (by an equally obscure, mysterious developer) about a broken girl and her broken dreams. This enigmatic title was Yume Nikki (2004).

Leading the charge, from both flanks, was the nascent independent (or “indie”) game scene, which set a precedent (which still holds to this day) of indie games and developers as the industry’s trendsetters, as well as the medium’s main fount of creativity, innovation, and artistry—not just for horror games, but indie horror certainly reflects this.

The Telltale Game(s): Narrative Adventures Come Back from the Grave

Video game adaptations of movies and TV shows have a reputation for being terrible, and for good reason—they usually are terrible. But like the proverbial broken clock, some adaptations are not only decent, not just playable, but actually excellent.

And Telltale Games’ adaptation of the graphic novel and hit TV show The Walking Dead was like the broken clock that lightning struck to make Marty McFly pierce the fabric of time.

Telltale was4 a studio that specialized in narrative-focused games (just in case the name wasn’t obvious enough), with an eye towards modernizing and reviving the story-driven adventure games of yore. Their secret sauce? The famous “Telltale Formula”:

A minimal amount of “traditional” gameplay; the player controls a character, but said character is very limited in what it can do and when (basically, don’t expect 3D Mario-type acrobatics)—a more technical term for this type of gameplay is “on rails”;

Linear, yet branching narratives—in English, this means the story begins the same way, ends the same way, and mostly follows the same plot beats with each playthrough (the “linear” part). But at the same time, the player can make choices that make the story unfold differently (the “branching” part);

Emphasis on the consequences of said choices, which often involve ethical dilemmas or needing to pick between two equally bad options, under a very short time limit. These decisions can greatly affect the story, even several chapters down the line (curiously, however, they almost never change the ending);

Quick, almost forced pacing that makes playing Telltale games feel more like watching an interactive movie or reading a graphic novel than playing a “game” (as the term’s commonly understood);

Heavy emphasis (bordering on overemphasis), as a central creative strategy, on adapting well-known franchises and IPs—including Batman, Game of Thrones, Back to the Future, and Jurassic World—into Telltale narrative games.

A proprietary engine, specially designed for Telltale’s choice-driven games, which—combined with game design that unwaveringly adhered to “The Formula”—allowed for relatively quick development cycles compared to the rest of the industry.

Telltale was founded in 2004, but had mostly huffed along until it launched The Walking Dead in 2012. That game caught players by surprise, racked up countless Game of the Year awards, put Telltale on the map, and heralded a new dawn for both story-driven games and zombie-themed horror games.

Unfortunately, only one of those new eras would live to see the end of the decade.

With The Walking Dead, Telltale became the standard-bearer for storytelling in video games. Telltale was living, breathing proof that good games could also tell good stories, be much better for it, and actually make money. Narrative designers everywhere owe the studio a massive debt of gratitude. But in a tragic and ironic twist that could’ve come straight out of one of its games, Telltale became a victim of its own success.

Since the “Telltale Formula” worked so well with The Walking Dead, the studio brass insisted on applying it to every game going forward—even long after the formula started feeling… you know, formulaic, and players lost interest. Creative stagnation had taken its toll, and even as the studio hemorrhaged players and sales, Telltale’s leadership was simply too scared to try anything else.

Eventually, the inevitable happened, and Telltale abruptly shut down in 2018. And it took hundreds of jobs, years of progress in advancing the cause of narrative in games, and the story-driven adventure game renaissance with it.

But zombies? Turns out that like their IRL inspirations, neither zombie games or survival horror games are killed off so easily. Throughout the late ‘00s and the ‘10s, AAA and indie studios alike would occasionally surprise players with titles like Dead Space (2008), Amnesia (2010), and yes, even some Resident Evil titles (Resident Evil 4 (2005) and Resident Evil 7 (2017) were particularly well-received).

Survival horror also branched out beyond zombies, to Lovecraftian abominations, aliens, and even sentient AIs.

Yes, really.

Neuromonster: Horror Brings Depth to FPS Games

You thought HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey was scary? That’s cute. Allow me to introduce you to the villainous AI from survival horror FPS System Shock (1994), the Sentient Hyper-Optimized Data Access Network (SHODAN):

SHODAN, the AI antagonist in System Shock and its sequel, is mostly like HAL… if HAL were female, an all-powerful narcissistic megalomaniac that stopped taking her medication before hijacking a space shuttle. You know, where she forced you at gunpoint to play Russian Roulette… with nukes. Wait, she’s still leaving you creepy voicemails, over six months later?! Jeebers creepers…

In both games, the protagonist (known only as “The Hacker”) is charged with neutralizing SHODAN before she can really muck everything up. But SHODAN, being a superintelligent AI with full access to and control of all the space station’s systems (including the ones involving weapons), seems to always thwart you at every turn. It’s like playing chess against Dr. Manhattan.

And to top it all off, SHODAN loves to taunt the player. As if getting your butt kicked by a frighteningly obsessive and codependent sequence of zeroes and ones wasn’t humiliating enough—no, you also have to endure getting dressed down and gaslit by a voice that sounds like the unholy amalgamation of Jigsaw and a drunk Transformer. It’s every bit as unnerving as you’re imagining. If you’re ok with not sleeping tonight, check out the following compilation:

The System Shock games also spawned a spiritual successor, in the form of the beloved BioShock trilogy (2007-2016), though those games were less survival horror5 and more about the horrors of mankind's stubborn and inevitably futile insistence on chasing utopia.

BioShock and its sequels left a multifaceted legacy that continues to inform everything from games as social commentary to environmental storytelling. These games really deserve a write-up of their own. For now, just know that this is a fantastic trio of games that’s well worth your time, regardless of how “good” you are at games.

Although not technically a “horror” game, Half-Life (1998) deserves a mention as another game that pioneered environmental storytelling and narrative quality that far exceeded expectations for FPS games. Besides, it has enough creepy monsters and scary sequences to merit an honorary inclusion in these annals.

Anyway, moving on!

Killer Games from Outer Space: Boldly Going Where No Zombie Has Gone Before

I’d be remiss in writing a history of survival horror and not including the Dead Space trilogy (2008-2013), two of which are among the most viscerally terrifying interactive experiences ever committed to code. But it’s the first entry (and to some extent, the second) that players remember most fondly. On the surface, Dead Space looks like “Resident Evil… in SPAAAAAACE!!!” …But appearances can be deceiving!

While Dead Space wasn’t ashamed to let its survival horror flag fly, the developers took full advantage of the space setting to add some very inventive space twists that allowed the space franchise to stand out amidst a (somewhat) still-crowded subgenre.

Among these “twists” were:

Going completely off the space rails with its

space zombieNecromorph designs. This, in my humble opinion, is far scarier than any of the space game’s space jump scares. Let’s put it this way… if space body horror freaks you out, you might want to skip this one;Subverting the “head shot = dead zombie” mechanic that’d become so ingrained in the survival horror genre. In Dead Space, space headshots do not kill space Necromorphs… uh oh;

An even bleaker space ending than is standard for survival horror.

So, even though survival horror was well past its peak popularity, it still had plenty of space creative space potential to space6 tap into.

And there’s no better example of this than The Last of Us, quite possibly the pinnacle of zombie apocalypse survival horror. Although quite unusually for a horror game, it’s much more likely to elicit tears than screams. This is thanks to its genuinely touching and moving story about the deepening bond between a jaded middle-aged dude and the orphaned girl he ends up taking under his wing.

It was such a universally beloved game that it spawned a(n unfortunately contentious) sequel, as well as an upcoming, live-action HBO series! Like Telltale’s The Walking Dead,7 it has also served as a living, breathing, proof-of-concept for a story-driven game that was also a blast to play, and highly profitable. Unfortunately, the sequel also serves as a textbook case study on just how impossible to please gamers can be.

A Nightmare on Game Street: Grassroots Games Build the Indie Horror Scene

“If I am mad, it is mercy. May the gods pity the man who in his callousness, can remain sane to the hideous end.”

~H.P. Lovecraft

[CW: mental illness, depression, complete social isolation, disturbing imagery, suicide]

While survival horror fans were getting stalked by computers and dismembered in outer space, players whose tastes in horror were less jump scare-ey were having fun of their own. They’d soon find themselves spoiled for choice of games exploring myriad neuroses, insanities, mental breakdowns, and every other conceivable ailment of the mind—as well as every imaginable way these mental afflictions manifest, no matter how twisted or deranged.

Yes, that good ole’ psychological horror we’ve been talking about would eventually dethrone survival horror as King of the Horror Game Subgenres.

And whether players knew it or not, they owed it all to a shadowy, anonymous developer—known only by their handle, “KIKIYAMA”—who dumped their game in a seedy internet back alley, dropped off the face of the internet, and left everyone scratching their heads ever since.

This game, Yume Nikki (“dream diary” in Japanese), left a profound imprint on video game horror—especially indie horror. One which we still feel today.

Yume Nikki is psychological horror distilled to its purest form and mainlined straight into your worst nightmares. To start with, the game itself is shrouded in mystery: Yume Nikki’s single, pseudonymous developer “KIKIYAMA” created it using RPG Maker (a famously straightforward and user-friendly game engine), uploaded it to a Japanese image board for anyone to download, and then vanished—seemingly into thin air, and leaving no trace.8

The game has since attained cult status, spawning countless imitators, homages, and conspiracy theories about the developer. It eventually got a fan translation into English, which spread its reach to Western horror gamers.

Today, Yume Nikki is routinely ranked amongst the scariest games, cited as an influence by horror developers (particularly indie developers) of all stripes, and considered required playing for psychological horror fans. It was also remade as a 3D platformer and re-released as YUMENIKKI - DREAM DIARY - in 2018 (naturally, the original is much better).

In Yume Nikki, you control Madotsuki, a hikikomori—basically, a modern-day hermit—living in a tiny studio apartment. The concept, history, and sociology of the hikikomori are far too complex and off-scope for us to cover in any way that remotely does them justice. But I’ll give you a simplified version, as this is one of this game’s central themes.

Hikikomori is Japanese for “pulling inward” or “being confined,” and it refers both to a behavior and the people who do it. In a nutshell, a hikikomori is an extreme recluse—often a teenager, young adult, or middle-aged professional—who suddenly and completely withdraws from society, confining themself to their room or home. There, they’ll spend every waking moment, never emerging from their dwelling for months, years, or even decades at a time.

That’s not an exaggeration, by the way. When I say they never come out, I literally mean NEVER. If they ever emerge at all (which is far from a given), they’ll do so only if absolutely necessary (for example, to buy groceries) and only when they’re least likely to see other people—usually late at night.

Though not all hikikomori are Japanese, it is a primarily Japanese phenomenon. Japan is host to a confluence of cultural and social factors—some universal, some unique to Japan—that enable and implicitly encourage the hikikomori’s extreme reclusiveness.9 But these are beyond the scope of this newsletter; just know that the game’s protagonist is a hikikomori.

Anyway.

While awake, there’s not much you can do. Madotsuki lives in a sparse studio apartment with only a bed, a desk (where you can save your game), a TV, and a game console. The TV and game console let you play a mini-game, but it quickly loses its novelty. You can go out onto your balcony, but there’s nothing to do but stand and look beyond the railing. And if you try to leave the apartment, Madotsuki—being a hikikomori—will simply refuse to open the door.

What’s left? The bed. Once you tire of moping around Madotsuki’s apartment, you can have her can lie on her bed, after which she quickly falls asleep and drifts off into her dreams… which you can watch below:

[CW: Epilepsy; flashing lights/colors. Do not watch if photosensitive.]

Yeah, I figured it better to let the game speak for itself. No matter how well I described this surreal, fantastic, and terrifying dream world, it’d have paled in comparison to just showing you.

You’re welcome.

Yume Nikki had little in common with Telltale’s The Walking Dead, but there was one big thread linking them: both games shared a disregard for established gaming conventions, and both games proved more than willing to throw it all away and try something radically different.

Yume Nikki has no dialogue, no tutorial, seemingly no objective, and nothing driving the game or the story forward. You simply, explore, and explore some more, until you’ve explored enough to have collected the right plot tokens to trigger the game’s (depressingly grim and bleak) ending. Obviously, it’s up to you to find these collectibles, as the game gives you no hints of what they are, clues to where they might be, or even any indication that you should be looking for anything at all.

But Madotsuki’s dream world is just so unremittingly strange that players feel compelled to explore it, just to see what awaits them behind the next door, or around the next corner. Sometimes, the dream suddenly turns into a literal nightmare, and Madotsuki’s inner demons descend on her—causing her to wake up, alone in her apartment again.

The player can then save her game at the desk, play some more of that mini-game, or fall right back asleep and descend into the dreamscape again.

A lot of Madotsuki’s dream imagery is extremely unsettling. Though jump scares are (mercifully) rare, simply wandering through her dreams can instill a creeping unease in the player—it’s obvious that Madotsuki is a deeply distressed and disturbed individual—and such use of atmosphere to generate fear is one of psychological horror’s time-honored techniques.

But perhaps even more unsettling is the ending, which the player would practically have to stumble upon, due to the labyrinthine requirements to trigger it, combined with the game’s complete lack of direction on how to do so.

So, after countless hours of haphazardly wandering about, checking every possible hidden corner for every collectible, and possibly being scarred for life after spending so much time in such an oppressively depressing world, a cutscene triggers! Well, that’s certainly different! And so, the player hopes Madotsuki has sorted out her problems, and is ready to venture out of her apartment to face the world…

…wait, Madotsuki, wrong door! The door to the hallway is that way. You’re going out into the balcony… wait, what is she doing? She’s climbing the railing… oh, no… no… no, no, no, no, no, NO! Madotsuki!! Don’t ju—

…aaaaand she jumps. Cue hauntingly depressing piano song, and roll credits.

The End.

…

……

………Geez. Even though we (thankfully) don’t see the impact, that’s a real downer of an ending, especially one the player has to work so hard for. But then again, depressing endings are another psychological horror staple.

[CW: Obviously! Just… don’t watch this video if your head’s not in a good place.]

Yume Nikki left such an impression on those who played it, that fans soon took to RPG Maker to create their own bleak and disturbing takes on this enigmatic game’s brand of psychological terror. Fans spawned so many of these games as to create a whole new subgenre: “explorer horror.” Several became highly influential in their own right. And a lucky few even got picked up by publishers, given full “proper” releases, and sold on digital storefronts like Steam. For real money.

Yume Nikki also firmly cemented East Asia in general, and Japan in particular, as the world’s most prolific exporter of psychological horror games. Very similar to how the original, Japanese versions of The Ring (actually a bonafide franchise in Japan!) and The Grudge did so for film.

Some of these include the Fatal Frame franchise, about an anime schoolgirl with a camera that can bind evil spirits, malicious specters, and nasty demons. Detention is similar game—this one’s from Taiwan—where you play as a student in a school that’s quite literally going to hell. And the less is said about Yumeiri, the better.

(You may have noticed a pattern of Eastern horror works being set in schools. I don’t have enough cultural expertise to speculate why, but I wonder if it’s partly a reaction to, or metaphor for, the crushing pressure for academic success that creates hikikomori like Yume Nikki’s Madotsuki?)

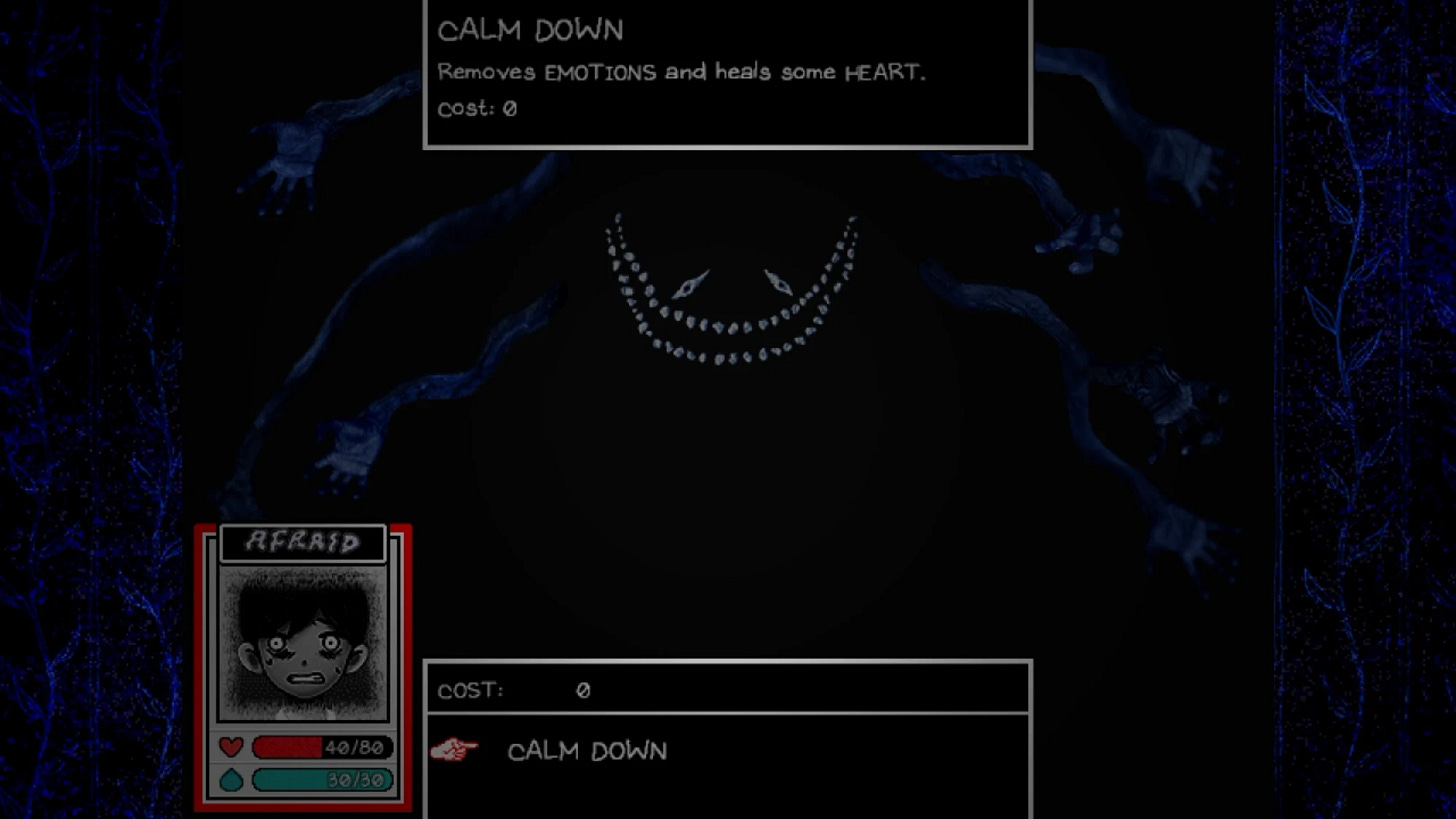

More recently, we’ve got the Japanese-inspired psychological horror RPG, OMORI (2020). The latter wears its Yume Nikki influence on its sleeve, namely through its intricately disturbing, highly reminiscent mindscapes, and even its very own hikkikomori protagonist!

We’re really just scratching the surface, too. The rise of indie gaming led to an explosion of titles from practically every horror subgenre, and indie horror developers are still going strong to this day.

Don’t worry, we’ll get to all those horror niches next week!

What’s Old Is Scary Again: Horror Gaming Comes Full Circle (Late ‘10s – Present)

The 2010s were a decade of monumental growth and change for the gaming industry. The indie scene, in particular, became the medium’s creative driving force, as smaller developers with smaller budgets took creative risks that mega AAA studios working with overbloated budgets would never even consider.

At the same time, as gamers who grew up playing games start having families of their own, AAA publishers have started digging into their vaults to re-release and re-master old favorites, hoping to cash in some sweet nostalgia bucks while also introducing classic games to a whole new generation.

This has all led to a proliferation of games of every conceivable genre that cater to any conceivable taste. Some would say we’re in the middle of a “Golden Age of Gaming” due to the sheer variety of experiences available to gamers today.

And so it’s been with horror, too.

Nowadays, horror games come in all shapes and sizes—cosmic horror, sci-fi horror, surreal horror, psychedelic horror, and yes, even those OG mainstays, survival horror and psychological horror, are still alive and kicking. Horror games have been made into games of every conceivable gaming genre, from FPS to Metroidvanias to RPGs graphic adventures to visual novels and everything in between.

Horror games are available on PCs and consoles alike, and they cater to some really specific preferences—are you more of a first-person player, but hate jump scares? There’s a game for you. Are you more of an RPG person, but loves jump scares? Somehow, there’s a game for you, too. Enjoy horror imagery but don’t actually like feeling scared? The buffet’s open, knock yourself out!

Oh, and are you a gamer of a certain age that pines for the jump scares and zombie shooters from your glory days? Well, old-school survival horror is coming back in vogue, with a vengeance. Both in terms of remakes/remasters to milk that sweet nostalgia cash, and brand-new IPs that keep the subgenre fresher than an exploding revenant.

In short, it’s never been a better time to be a horror game player. But this leaves the question—now that scary games offer every possible fright one could seek, where will horror gaming go next? Where can it go next?

You may have noticed a pattern throughout the genre’s history—it latches onto trends to such a degree you’d think its life literally depends on it. Which means that wherever the industry goes, so goes horror. And recent signs are… not very encouraging.

To illustrate, take a look at the AAA horror slate for 2023:

Looks good on the surface, right? But think about what you’ve just read over the past two weeks. Don’t those names look familiar? Yup, if you’ve been paying attention, you’ve already figured it out—all but one of the games on this list are remakes, and the only non-remake (Alan Wake II) is a sequel.

This mirror’s the sordid trajectory Hollywood’s been trudging for decades. As budgets swell and markets change, creative risks are becoming all but verboten to the major Hollywood studios. As such, almost all big-budget movies these days are sequels, remakes, or formulaic, played-out retreads.

There are signs the video game industry is following Hollywood down that same path, which shouldn’t be a surprise at this point. As we’ve pointed out several times at Game & Word, film and gaming have followed such similar trajectories that to see where gaming is headed, all we need to do is see where Hollywood is now.

Gaming’s major AAA publishers are just as anxious as their Hollywood counterparts to recoup the ever-ballooning costs of production (and game development was already expensive enough!). So like the major film studios, they mostly stick to what’s safe. That’s why we have 200 or so Call of Dutys, 1,500 or so Battlefields, and a gajillion zillion trillion Maddens and FIFAs—all of which are essentially the same game with a few tweaks, re-packaged as a new game and re-sold at full-price every year.

Now, I’m not saying that all these blockbuster AAA releases are bad games. I doubt they’d sell as well as they do if they weren’t at least decent. There’s certainly a big market for them! But big-budget games do feel more formulaic, repetitive, and derivative with each new release.10

And the sad part is, in order for creative innovation to take place, you don’t even need to scrap these successful IPs, or the genres/subgenres that spawned them. You just need to do something new with them.

But considering the massive development budgets I’ve already mentioned, combined with diamond-hard player hostility towards change,11 don’t expect the AAA space to lead the charge.

However, not all is lost. There is still hope for the medium, and it comes from—can you guess?—the indie developers of the world. These are the heroes that consign themselves to lives of backbreaking toil and the ever-present risk of complete financial ruin. All to keep gaming’s creative and artistic spark alive and burning.

The Future Is Terrifying (But in all the Right Ways)

To illustrate, let me show you how indie devs are breathing some much-needed creative oxygen into very established subgenres. The resulting games combine the best of old and new—they offer the comforting familiarity of an established genre by adhering to its conventions, while also presenting them in novel and inventive ways.

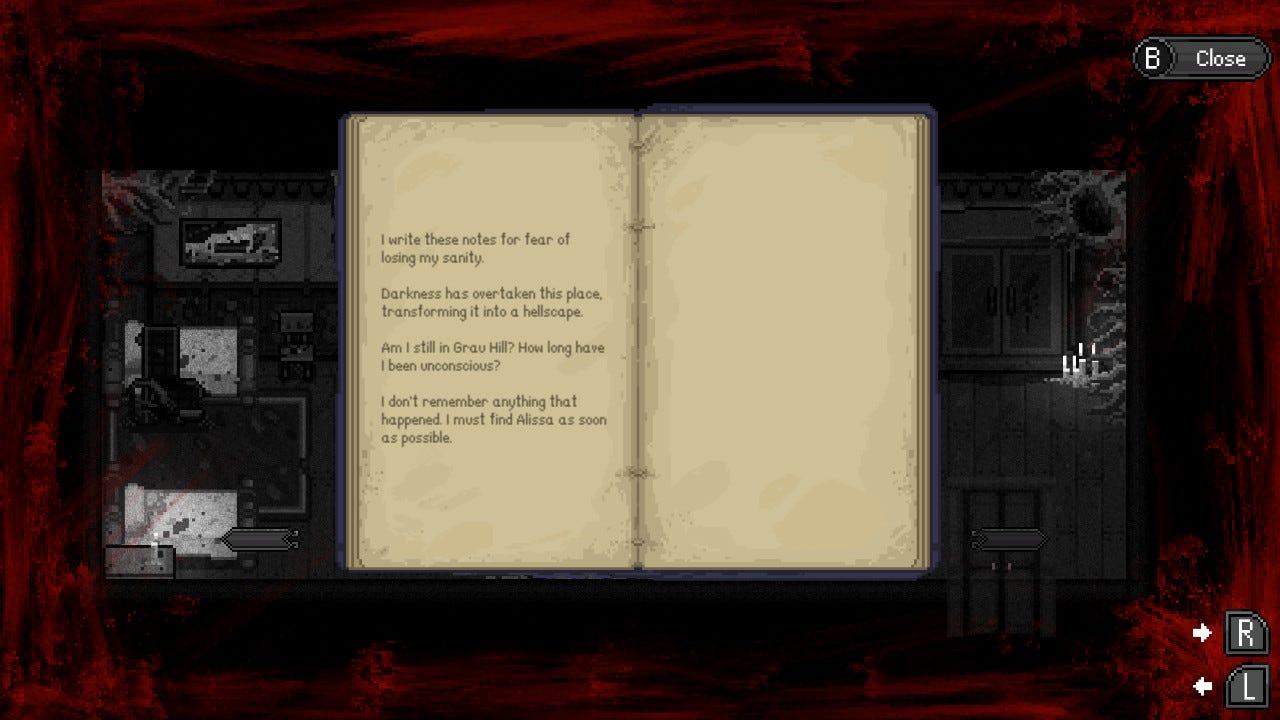

Let’s start with survival horror, perhaps the textbook horror gaming genre. While Capcom’s busy remaking Resident Evil 4 (a game from 2005), indie developer Obscure Tales’ brilliant Lamentum (2021) takes all the frights and gameplay ticks of old-school survival horror. But it also eschews the third-person gameplay and hyper-realistic graphics, opting for a pixelated art style and top-down perspective that’d feel right at home as a 90s 2D Zelda title. And instead of modern-day cops shooting zombies, you’ve got a gentlemanly ole’ chap wandering a Victorian gothic manor desperately fleeing stomach-churning, Lovecraftian monstrosities.

Or perhaps you prefer psychological horror? Instead of replaying Silent Hill 2 for the 17th time, try UK indie studio Cloak and Dagger Games’ The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow (2022). Here, the developers took a gaming genre with one of the medium’s oldest pedigrees—point-and-click adventures—and streamlined it for the modern age. Then they threw in a veritable potpourri of horror techniques and references, for good measure.

The game’s setting—a remote, decaying English village in the middle of a desolate moor—drips with the ineffably unnerving, “something’s-not-right-but-I-can’t-put-my-finger-on-it” malaise that’s a hallmark of psychological horror. But that’s not all—it also masterfully blends in elements from surreal horror, cosmic horror, gothic horror, and especially folk horror (which is seeing a contemporary resurgence of its own, across all media).

Hob’s Barrow combines one of gaming’s oldest genres (graphic adventures) with one of horror’s most overplayed subgenres (psychological horror), then binds them together with myriad homages to everything from folklore to Lovecraft. And it wraps it all up with perfect narrative pacing, superb voice acting better than most movies, and just delightfully creepy art direction and sound design.

As a result, Hob’s Barrow sets the high-bar for point-and-click adventures, psychological horror, folk horror, and storytelling in games. And while undoubtedly inspired by prior works (the game makes no effort to hide this), it’s not a sequel, remake, reboot, or remaster.

With both Lamentum and Hob’s Barrow, we get something old and new. But most importantly, these games give players a creepy, unnerving, and scary experience—you know, the whole point of horror to begin with—without endlessly falling back on retreading old works.

If horror truly holds a mirror to our faces, then the future of horror games will mirror the future of the video game industry. In that case, plucky indie studios or solo developers will continue to serve as the medium’s creative trailblazers. By combining, constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing genres and conventions, these games will frighten and amaze players in ways nobody had ever thought of before.

Then, more indie devs contribute their own interpretations, sanding over initial rough spots, and bringing their own diverse perspectives to the table. Lo and behold, a subgenre is born!

After a while, the AAA studios will sense the start of a profitable trend and hop on the train, using their practically bottomless pocketbooks, top industry talent, and impeccable production values to create bigger, better, and scarier takes on this scary new subgenre, until…

…About a dozen sequels and seven reboots later, when the trend has clearly burned out, and what used to be new and scary has become an old, trite, and derivative ashen husk of what it was. Something even newer is needed, but none of these mega-corporations dares to put their hundreds of millions of dollars on the line and take that first leap of faith. And so, the subgenre continues to wither and stagnate…

…Until another crafty, creative indie developer manifests another flashy, new, scary trend. And so, the cycle continues, until the end of time itself…

Well, that is unless Mark Zuckerberg somehow doesn’t manage to kill virtual reality (VR) with his fake “metaverse” grift, and/or government regulators finally grow a spine and force Meta to spin off Oculus, so it can finally spearhead the technology unimpeded.

Then, we’ll get to experience the ultimate horror experience ever conceived: fully immersive horror VR games!

…Wait, what? That’s already a thing?!

…

Well, sh🤬t…

—

And, that’s a wrap, folks! Join us next week for the Halloween Special goup de grace: The Game & Word Halloween Codex, a haaauuuunted guide to the best horror games that cater to everyone, from the scarediest of cats to the most hardened of monster hunters.

See you then, and remember: if you and your friends find yourselves trapped in a creepy house with a deranged serial killer and no way out… for the love of all that is good and holy, DON’T EVER SPLIT UP!

Food for Talk: Discussion Prompts

While you wait for the next issue, I invite you to mull over the following discussion prompts. Please reply to this email with your answers, or post them in the comments—I'd love to hear your thoughts!

What’s your preferred flavor of horror, and why? Does your preference change for each medium, or is it consistent across all media?

What’s your favorite horror game, and why? Or, if you’re not a horror gamer, your favorite horror story, regardless of medium?

Have you ever played a horror game so intense, you weren’t able to finish it purely out of fear (so: not out of boredom, attrition, or other reasons for abandoning games)? If so, which was it, and what did you find scary about it?

Further Reading

NOTE: The following list may contain affiliate links, which give me a tiny cut of any purchases made through the link. this helps keep the newsletter sustainable.

The Walking Dead: Volume 1 by Robert Kirkman — You’ve watched the show, played the game, now read the graphic novels that started it all.

Silent Hill: Lost Memories by Konami — If you feel drawn to the bizarre and twisted world of Silent Hill, this translated transcript of a rare, straight-from-the-developers compendium of in-universe lore is the perfect late-night rabbit hole to dive into.

The Rise and Fall of Telltale Games by Game Informer — Perhaps the most tragic cautionary tale in all of gaming, this is a riveting account of the former indie darling’s shocking fall from grace, as told by the people who saw it all go down in flames.

Games Featured:

NOTE: The following list may contain affiliate links, which give me a tiny cut of any purchases made through the link. this helps keep the newsletter sustainable.

Silent Hill, developed and published by KONAMI — Franchise Portal

Telltale Presents: The Walking Dead, developed and published by Telltale Games — PC | iOS | PlayStation 4 | Xbox One | Nintendo Switch

The Last of Us, developed and published by Naughty Dog — PlayStation

Yume Nikki, developed and published by KIKIYAMA — Steam | Softonic | iOS

YUMENIKKI – DREAM DIARY –, developed by KADOKAWA CORPORATION, Active Gaming Media, Inc., published by Playism — Steam | Nintendo Switch

Dead Space, developed and published by Electronic Arts — Steam | Origin | PlayStation 3 | Xbox 360

System Shock, developed by LookingGlass Technologies, published by Origin Systems — Good Luck!

BioShock, developed and published by 2K Games — Steam | Nintendo Switch | Xbox One | PlayStation 4

Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water, developed by Koei Tecmo, published by Koei Tecmo/Nintendo — Nintendo Switch [Physical] | Nintendo Switch [Digital]

Detention, developed and published by Red Candle Games — Steam | Nintendo Switch

OMORI, developed and published by OMOcat LLC — Steam | Nintendo Switch | PlayStation 4 | Xbox

Lamentum, developed by Obscure Tales, published by Neon Doctrine — Steam | Epic Games Store | Nintendo Switch | Xbox | PlayStation 4

The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow, developed by Cloak and Dagger Games, published by Wadjet Eye Games — Steam

Game & Word-of-Mouth: How to Support My Work

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this content and would like to read more of it, there are many ways you can show your support for Game & Word. First, hit the heart button at the bottom of the post—it really helps with my discoverability! You can also show your support by sharing this issue with your social networks and subscribing to Game & Word (if you haven't already).

Finally, if you haven’t upgraded to a paid subscription, well, that’s the best way to support this publication. You can upgrade your subscription using the following button, or in your account settings (note that you can only upgrade your subscription on the web, not through the app):

See you next week!

Tags

#history #narrative #storytelling #narrative #horror #halloween #culture #psychology #art #film #TV #literature #ludology

#TempusLudos

#SilentHill #TheWalkingDead #YumeNikki #DeadSpace #SystemShock #BioShock #HalfLife #Omori #Lamentum #TheExcavationOfHobsBarrow

Footnotes

Or their close relatives, who despite being civilians, are somehow equally good shots.

And, by extension, the player.

Another possible contributing factor: a parallel surge of psychological horror in film. Requiem for a Dream (2000), The Ring (2002), The Grudge (2004), and even Silent Hill’s own atrocious film adaptation (2006) all came out during the rise of psychological horror in games.

Yes, “was.” But it’s being revived!

Though still spooky in their own right.

[ED. NOTE: Ok, we get it!!! It’s in SPACE.]

You know, the other zombie apocalypse game about a world-weary man reluctantly becoming a surrogate father figure to a more hopeful and idealistic child, only to end up genuinely caring for her, making their ultimate fates all the more heart-wrenching.

Supposedly, the developers of the recent Yume Nikki 3D remake were able to track KIKIYAMA down for permission to remake the game. But even this turn of events is shrouded in mystery, and some within the fandom even dispute its occurence.

While the phenomenon’s still poorly understood, researchers have identified a few likely culprits, working in tandem with each other.

First, there’s the staggering amount of pressure Japanese culture places on youth to succeed academically, and on adults to live a socially-sanctioned life of rigid conformity and chronic workaholism—and thus reflect well on their family. Easier said than done in an economy that’s remained more or less stagnant since 1991.

Often, this proves to be too much, and when someone finally buckles under the pressure, they may choose to entirely withdraw from society as a defense mechanism. This is especially so for people with severe mental illness or a developmental disorder, neurodivergent people, or people who can’t or won’t conform to societal expectations for a multitude of reasons.

Obviously, acute societal pressure to suceed isn’t limited to Japan—indeed, this is common throughout East Asian cultures—and there are people with mental illness, developmental delays, and autism everywhere in the world. But there are other factors that enable a person who shuts themself in their room to remain shut in their room. Some are more universal—like the proliferation of the internet and, yes, video games—but others are more distinctly Japanese.

Japanese parents of hikikomori are often in denial about their child’s descent into complete isolation (or have a codependent relationship with them). If a hikikomori suffers from comorbid mental or developmental challenges, it’s even worse—such conditions are so heavily stigmatized that even an admission of what’s going on is perceived as shameful. As such, parents with the resources to provide for their adult child indefinitely, will do so—bringing them food and doing their laundry—thus enabling the hikikomori to remain shut off from society for a very long time (on the flip side, this also means that hikikomori almost always come from middle- and upper-class families).

Finally, the internet-enabled advent of remote work and on-demand entertainment, along with the still-ongoing rise of the nighttime economy, make it possible to live completely devoid face-to-face contact. The former factor is a fact of life worldwide, but the latter factor is especially pronounced in Japan, where 24-hour convenience stores have highly prolierated, as well as (especially) vending machines that dispense anything and everything one could possibly need. No human interaction required.

Oh, and that’s not even accounting for the pandemic, which may well make hikkokomori a global phenomenon—if it hasn’t done so already.

Probably because they are formulaic, repetitive, and derivative, and each new release simply makes it more obvious.

Nurtured by the publishers themselves, through decades churning out near-identical sequels and re-releases—a feat that even McDonald’s would begrudgingly admire.