NOTE: This article was originally published on Medium on June 21, 2019. It went viral the next day, generating over 9,000 upvotes on r/NintendoSwitch, multiple Reddit awards, and over 10,000 views on Medium within the next two weeks. We are listing it here as a “Greatest Hit,” since it’s a perfect example of Game & Word content at its best.

Table of Contents1. Introduction

2. Video Games: Disease or Cure?

3. My Story

4. Stories from Others5. The Science of Zelda Therapy

5.1 Trauma and Growth

5.2 A Healing Story

5.3 Cure of the Wild

5.4 Elixir Soup for the Soul

5.5 The Power of Friendship

5.6 But Why Breath of the Wild?6. The Dark World of Gaming Addiction

6.1 An Unfortunate Misdiagnosis7. ConclusionSPOILER WARNING: This post may contain spoi — ah, come on. You’ve already played Breath of the Wild by now. And if you haven’t, then A) what the hell are you even doing with your life?! And B) this post contains screenshots that *might* be considered mild spoilers. Without context, I don’t see how they’ll spoil anything, but if they do, I don’t want to hear about it. You’ve been warned.

Introduction

NOTE: Names have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Omar was depressed because of his legal issues. Sarah deals with Seasonal Affect Disorder every winter. Zeke suffers from agoraphobia, anxiety, and panic disorder.

All three have recently found a surprising source of comfort, solace, and relief: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

“This game saved me from severe depression while going through some legal issues,” says Omar. “[I] was always a big fan [of Zelda] growing up, and this masterpiece really helped take my mind off of things out of my control when I needed it most.”

“When I felt alone, I’d turn to this game,” Sarah explains. “I have some family health issues too that are quite depressing, so again I’d turn to Hyrule to forget [about them] for a little while.”

“Panic and anxiety tend to make you self-destruct and spiral out of control,” says Zeke. “[Breath of the Wild] keeps my mind away from self-destructive thoughts.”

These are just a few of the people on Reddit and Discord who shared with me their experiences of playing Breath of the Wild as a form of self-care. Players everywhere are using the game to help them overcome trauma, cope with depression, and find peace in their final days.

Healthcare, particularly mental healthcare, remains out of reach for millions of uninsured Americans; and even those with healthcare access are only a job loss, rate hike, or Supreme Court decision away from losing it.

Even people with good insurance, or who live in a country with universal healthcare, are often reluctant to seek help for mental health issues. Privacy concerns and the enduring stigma associated with mental health treatment continue to act as deterrents and barriers.

So, people seek relief elsewhere; and for many gamers, video games offer the mental salve they need to keep pushing when life feels like it’s unbearable.

Video Games: Disease or Cure?

That video games could have therapeutic potential seems not only plausible but obvious.

Video games as self-care — or even therapy — may seem like a strange concept, especially from a non-gamer’s perspective. Indeed, most mainstream discussion around gaming treats it as something you’d use therapy to cure rather than a source of treatment itself.

From this point of view, video games are, at best, a waste of time — useless to the mind, devoid of educational value, and anything but therapeutic.

At worst, video games constitute an insidiously addictive and detrimental social plague that turns kids into either spaced-out zombies who resemble heroin addicts or maladjusted and angry shut-ins who express their rage by emptying an M-16 clip onto a crowd of strangers (à la Grand Theft Auto).

Indeed, according to mainstream society, video games are a scourge — and should be dealt with accordingly. Officials in the Indian state of Gujarat banned battle royale shooter Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) over concerns of addiction and violence. PUBG was also a casualty of China’s recent crackdown on gaming, spurred by similar concerns. And after every school shooting in the US, video games are inevitably scapegoated.

These are just a few examples of the tendency for governments and moral entrepreneurs to depict video games as a social illness to be quarantined or eliminated — quite literally now that the World Health Organization has added “gaming disorder” to its International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11).

But amongst gamers themselves, that video games could have therapeutic potential seems not only plausible but also obvious. Increasing numbers of us are turning to games during periods of stress and trauma. We understand, firsthand, the power our hobby has to heal and to bring relief.

Furthermore, gamer psychologists and therapists are effectively integrating video games into formal therapy, providing a glimpse of a future in which the mental health profession accepts — and even embraces — video game therapy as a legitimate form of intervention.

And while any game can be therapeutic — Stardew Valley and Fortnite (yes, THAT Fortnite) are two games that often pop up in this context — there are few, if any, games that can match Breath of the Wild’s therapeutic potential.

I know this is true because I have personally experienced its healing magic.

My Story

Breath of the Wild quite literally saved my mental health — and likely my life.

Like so many other players, I was immediately taken in by Breath of the Wild’s vast and open world, its awe-inspiring attention to detail, and its strategy-focused combat system. I’ve already written about that elsewhere and so I won’t re-hash it here.

I’ve also written about how, barely a month after Breath of the Wild launched, my daughter was born — and promptly rushed to the NICU for the first of two open-heart surgeries and a 90-day stay at the hospital.

It’s hard to impart to others just how grueling it is to see your child hospitalized. Unless you have experienced it with your own child, your imagination cannot do it justice. It is pure torture — there’s no other way to put it.

Those who’ve had loved ones hospitalized will tell you that the most maddening part of a hospital stay is the waiting. In between appointments and procedures, there are hours upon hours, days upon days, even weeks upon weeks of sitting around and waiting. And waiting some more. And waiting still even more. Time slows to a crawl.

It’s enough to lead your mind to wander to some very dark places.

There was one thing, however, that pulled me back from the brink of mental collapse many times over: Breath of the Wild.

On more occasions than I could count, I would turn on my Switch and, like Link looking into the Magic Mirror, transport myself to the world of Hyrule for a couple of hours. By the time I had turned the console off, all my worries had disappeared — at least temporarily. It was what I needed to carry on.

Switch on, tune in, switch out. I’d repeat this routine again and again as a way to psychologically survive until the next appointment or procedure. By keeping me sane, Breath of the Wild made it possible for me to maintain hope that someday soon my family and I would finally be able to go home.

That hope is what kept me going until one day, we finally did get to go home.

Breath of the Wild quite literally saved my mental health — and likely my life. I will be forever grateful to it.

And I’m not the only one who feels this way.

Stories from Others

Michelle got the game in December as a gift from her significant other. A big Zelda fan, she was instantly hooked — drawn to its gorgeous visuals, freedom of movement, and immersive qualities.

Then, tragedy struck.

“I lost my cat to a sudden illness, and broke up with my significant other in the same week,” she wrote. “I also have anxiety issues. The game has been incredibly helpful to cope and take my mind off things.”

“I love this game,” she exclaimed.

Like Michelle, Pat plays Breath of the Wild whenever his emotions get the better of him. He used the game to bond with his younger sister (who was making her own way through the game at the same time) as well as with his girlfriend.

“Our relationship greatly improved,” he says. “We played for hundreds of hours. And after a lot of long-distance, [my girlfriend] and I are finally together, and I get to watch her experience her first hours [of Breath of the Wild] just like my sister did with me. It’s amazing.”

Beyond improving his real-life relationships, Pat formed meaningful bonds with in-game characters.

“I met Farosh, the dragon,” Pat says. “He always seemed to show up when I had the controller. It made me feel so special and connected to the game, like Farosh had personally found me acceptable and wanted to be around me.”

Breath of the Wild can help not just with emotional pain but with physical pain as well. This has been Rachel’s experience — a gamer who deals with back pain.

“Just playing and forgetting the pain helps,” she says. “It takes my mind off of things that may make me irritated or sad. Instead, you see little things in the game that shift your focus.”

The staggering attention to detail that the latest installment of the Zelda franchise offers is simply unmatched. When immersed within all that detail, your problems effectively fade into the background — after all, those Korok seeds are not going to find themselves!

The Science of Zelda Therapy

So, why does Breath of the Wild seem to have such healing potential? I discussed this at length with Anthony M. Bean, Ph.D., a licensed clinical depth psychologist and editor of The Psychology of Zelda: Linking Our World to the Legend of Zelda Series. I also talked to Larisa Garski, LMFT, a practicing clinician who specializes in gamers, geeks, and others ‘outside’ the mainstream. Both Anthony and Larisa operate clinics that integrate video games into therapy, and both are avid gamers and Zelda fans.

I asked them why Breath of the Wild seems to help people cope more effectively with emotional and psychological stress and even overcome trauma and other forms of adversity.

Their answers were fascinating.

Trauma and Growth

“It sounds like Breath of the Wild has really been a touchstone for people when it comes to the opportunity that it fosters for healing, and having in-game cultivation of things like mindfulness,” says Garski. “And the game is also such a great example of pain’s power to transform us and help us to discover who we truly are, and who we want to become.”

Garski, who specializes in post-traumatic growth — even contributing a chapter on it to the Psychology of Zelda book — cites Zelda’s character arc as an in-game example of such transformation: “All the way through that painful process [of awakening her power], she doesn’t give up. It is the very epitome of what we hope post-traumatic growth can be. Just because something is hard and painful, it doesn’t preclude our ability to grow from it and even become stronger.”

Over time, the gamer internalizes this message and experience, if only subconsciously. This effect, called psychoanalytic projection, is incredibly powerful on its own; and the interactive nature of video games serves to amplify it to a much greater degree.

“As we play the game, we project our inner psyche, our self onto the game, into the characters we’re playing as,” says Bean. “As the character we control changes, we then have to reclaim that change, because it speaks to who we are as a person.

“So with Zelda, and Link, and Ganondorf, Demise, all of them, we project a part of ourselves onto [them],” he continues. “We work towards cleansing our self. When we drop a game, all that comes back into us. That’s what makes us feel a bit more calm, to be like ‘Wow, I accomplished a lot!’.”

A Healing Story

Players also project themselves onto their interactions with NPCs (non-player characters), and Breath of the Wild has many memorable ones. This provides further avenues for growth and learning.

“Stories, for [my patients,] are foundational to how they have learned to understand themselves and their place in the world,” says Garski. “And the characters in the story — they have formed really important relationships with those characters.

“[T]hose kinds of relationships have the power to help us do things like practice social skills, and help us do things like feel seen, feel validated.”

In short, Zelda allows us to breathe, grow, and understand a deeper part of ourselves as we progress through the game’s story. Stories are one of the most powerful agents for change human beings have ever discovered, tracing back to when our ancestors first started telling stories to their fellow tribespeople around bonfires.

Stories are powerful: they bring us closer together, inspire us to action, and even alter our very neurochemistry. As a story plays out, our brains release cortisone to make us root against the villain and oxytocin to connect us with the heroes.

When these hormones mix, a phenomenon called ‘transportation’ occurs: the induced attention and anxiety join with empathy, and for the remainder of the story the characters’ fates become our own.

If the story concludes with a happy ending — and most stories do — we feel as happy and optimistic as the characters do. If we find a story to be particularly resonant, its effect on us can be deeply transformational, persisting long after the narrative has concluded.

So, was Breath of the Wild just a story that spoke to me and to endless folks on Reddit at a time when we most needed to hear its message of perseverance? Did we, perhaps, subconsciously seek out that story or somehow know to stick with it once we started playing?

“I do think these stories have a way of finding us when we need them to,” says Garski, who frequently uses narrative therapy in her practice. “But, how much of [the healing] is through the story itself? How much of it is that this was a moment when we really needed it?”

That is indeed the key question. While Breath of the Wild certainly has a compelling and relatable story, it is not unique in this regard — even amongst Zelda titles. The series is known for its captivating (if convoluted) lore. All the same, Breath of the Wild seems to hold unusually great potential for therapeutic change. So, what else could be at work here?

Cure of the Wild

Perhaps Sam’s story can shed some light. Like most of the people I spoke to on Reddit, he felt noticeably calmer while playing Breath of the Wild. Eventually, he moved on and started playing Borderlands 2.

“I started noticing I was feeling really anxious and kind of wound up a lot of the time,” he explained. “After a few weeks, I decided to play [Breath of the Wild] one night and was shocked to find all of the anxiety and tension melted away. Just running around Hyrule, finding Koroks, and working on the handful of stray side quests put me at ease.”

Why could that be? Sam gives us a clue. One day, he was out riding his mountain bike in the forest; while alone in the wilderness with nothing but the wind blowing and the birds chirping, he started thinking of Breath of the Wild.

“At first, I was ashamed to think of a video game in such a serene situation,” he writes. “But then I thought about how perfectly the game captured what it’s like to truly be in the outdoors.”

Ah, the great outdoors!

Now, it’s impossible to talk about Breath of the Wild without mentioning its depiction of the world of Hyrule. It is massive — as big as Manhattan — and the game places practically no restrictions on your ability to explore it. ‘Immersive’ just doesn’t do it justice. The game all but transports you into its reality; and despite its fantastical elements, it feels a lot like our world.

“You can exist in the [game] world,” says Garski. “There you are, and you can cook a meal, you can walk through the forest, there are all these really fun mini-games. You are in the world, and you are moving in the world, and it feels both expansive and immersive and quiet.”

Technology, of course, is an enabling factor here.

“I’m sure Nintendo would have done it for Ocarina of Time if they could have, right?” says Garski. “But we’re at a point right now, technologically, where you can create a very life-like simulation of what walking through Hyrule would feel like. And they do that in the game so beautifully.”

Because we’re primarily visual learners, our neurons ‘mirror’ what we see. As a result, watching someone else — even a fictional character — do or feel something is like doing or feeling it ourselves.

In essence, when you play as Link walking through Hyrule, your brain thinks you really are walking through Hyrule.

In fact, several of Bean’s patients will turn on Breath of the Wild just to sit Link down in a safe space and listen to the game’s music and sounds while slowly taking in the vistas.

“That type of scenario is what we call ‘mindful,’” he says. “Being aware of their surroundings, while still within their own self. Sometimes, when they get really overwhelmed, they’ll just boot up the game and go stand somewhere.”

“They’re like, ‘I feel a little bit more relaxed.’”

Elixir Soup for the Soul

Given that a trove of research points to the benefits of both mindfulness and being in nature, it makes sense that immersion within Breath of the Wild’s Hyrule can lead to therapeutic effects. And for those who aren’t able to be in nature because of limited mobility — say, those who are hospitalized — it could be a godsend.

“Maybe you can’t walk right now, you’re certainly not going to be able to make your own food while you’re hospitalized,” says Garski. “But if you’re playing Breath of the Wild, and Link, your avatar, is making food, it lights up those mirror neurons in the brain.”

“So, emotionally, you start to feel very similar to the way you’d feel if you were at home making food,” she continues. “And that feels familiar. It feels like moving more towards health. It feels like, ‘Oh, I’m getting closer to returning to these parts of my life that I miss, that I enjoy.’”

The game also presents opportunities to experience things one would not ordinarily experience — and that’s beside the obvious ones like collecting magical golden triangles and slaying giant boar demons. If one looks hard enough, one can even find themes like family cohesion and love — sadly, elusive concepts in many Western households.

The Power of Friendship

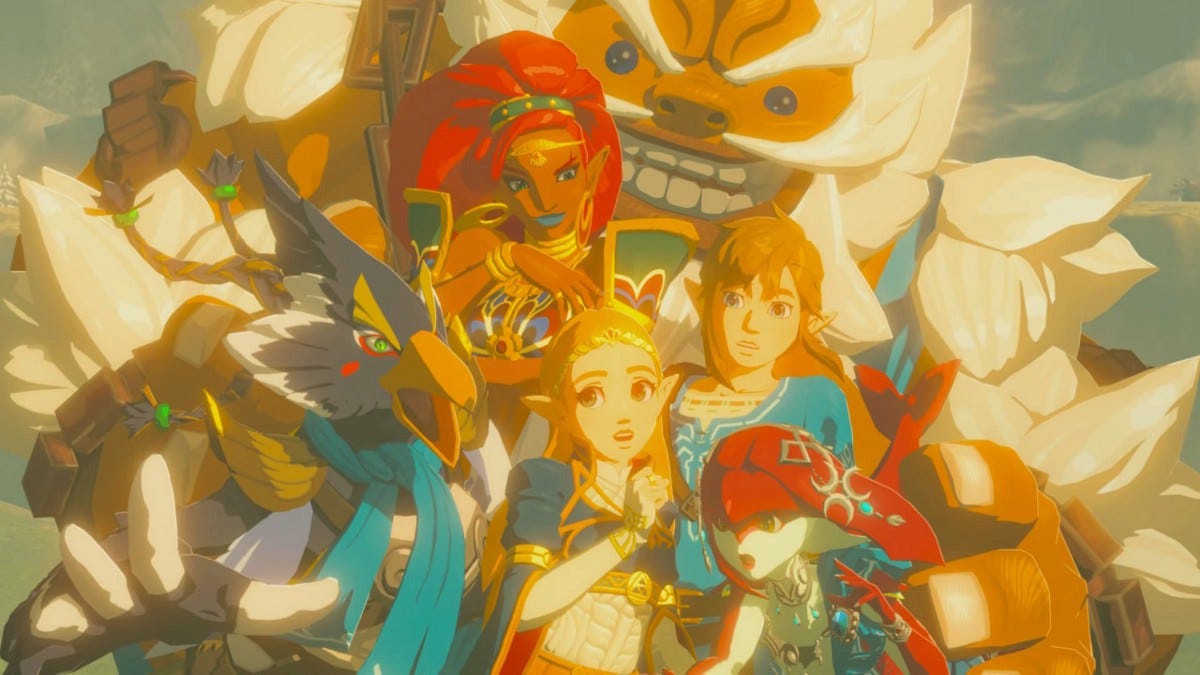

Link has long been a kindred spirit to orphans worldwide. Throughout the Zelda series, his family is seldom mentioned; sometimes, his loved ones are even killed at the outset of the story. Playing as Link thus provides people with the chance to cast off the shadows of their upbringings and to become heroes. But there’s more to it than just this in Breath of the Wild.

“It’s so subtle,” says Bean, citing the appearance of each Champion after Link slays a Blight Ganon. “These guys from 100 years come back, and they’re like, ‘Hey, I knew. I was proud of you for this.’ They’re not really physically there, but there’s still that resemblance of that family, that cohesion, that the game masters so, so well.”

The bond between Link and Zelda is another example. Zelda has been fighting Calamity Ganon for 100 years; only by cooperating do Link and Zelda manage to defeat the scourge.

“That really shows that they relied on each other so heavily that they were able to overcome it, as a cohesive family,” Bean says. “That feeling of acceptance, of knowing that you may be the last hope, but you still have all this support.”

Support networks are, of course, vital to our individual and collective survival. Even a simple expression of “I’m here for you” can give someone the strength they need to keep trudging through a hopeless situation. Even when this support comes in the form of the actions or words of a video game character, it’s still impactful because our mirror neurons make it so.

Subtle or not, the subconscious registers it and it has an effect.

But Why Breath of the Wild?

This is not to say other games can’t be therapeutic — virtually any game has the potential to help people cope with stress and emotional trauma. But not all games or genres are created equal. And as we’ve seen, Breath of the Wild has so many therapeutic touchpoints that it could very well be unmatched in its healing potential.

“I can’t help but compare a loot driven game like Borderlands 2 to a casino and [Breath of the Wild] to a hike through the woods,” Sam writes. “Both make you feel good, but the casino eventually backfires, whereas the wholesomeness of the hike is actually good for you.”

The Dark World of ‘Gaming Addiction’

“Most of the people we’ve [seen being] so against video games have never touched a controller in their lives.”

So, to recap: Breath of the Wild can be a catalyst for growth, mindfulness, and self-acceptance (to say nothing of its power, as a cultural touchstone, to bring people together), all of which give the game its highly therapeutic qualities. But even though the game shows great promise, is there another side to it?

Can too much of a good thing become detrimental?

This brings us back to the anti-gaming hysteria currently sweeping the world. Even though those behind the moral panic express worries that sound ridiculous to the average gamer, there is a kernel of truth to their concerns.

After all, many modern games are designed to be addictive — some brazenly so. And every gamer has a story of how they remained glued to their TV, controller in hand, until 2 am, even though they had to be up at 5 am the next day. Indeed, it’s practically a gamer cliché that expansive, open-world games are life-wreckers because they’re so hard to stop playing — and we all know at least one World of Warcraft aficionado.

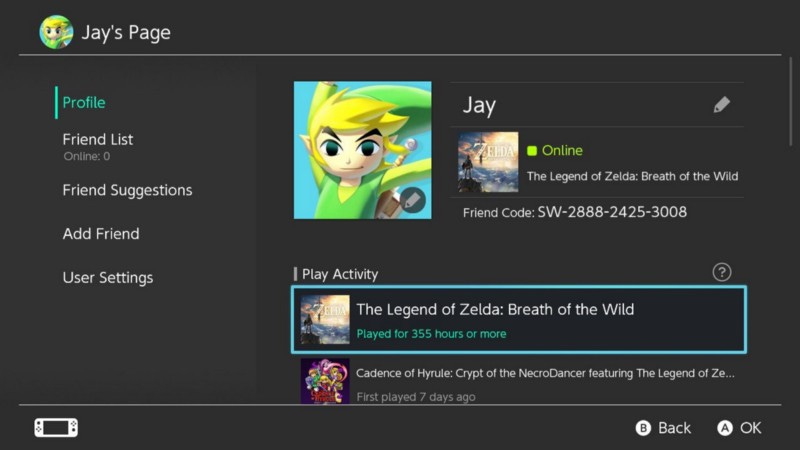

So, how much of a good thing is too much? I’ve poured over 350 hours into Breath of the Wild, but that was over a two-year period. If I had played that much in just two months, I wouldn’t consider that healthy.

Is there a point at which gaming becomes a legitimate concern? Do the moral crusaders and the WHO have a point?

An Unfortunate Misdiagnosis

“The way that they’re proposing that it currently exists, I do not think that it exists in that format,” says Bean, who is highly and vocally skeptical of the WHO’s classification. “They’re not informed by gamer culture. They’re not even trying to understand video games from what they do instill in people, or the possibility of therapeutic approaches, understanding oneself, personality development, or identity formation.

“Most of the people we’ve [seen being] so against video games have never touched a controller in their lives.”

“Now, this is not to say that it doesn’t occur somewhere, because we’ve all seen videos of kids playing 20 hours a day, not going to school, stuff like that,” he continues. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it does exist, to a degree. But to me, that speaks to an enabling culture and just really poor boundaries.”

“We need a lot more research on it,” says Garski. “I think that the term [‘gaming addiction’] gets thrown about pretty loosely. And that makes me concerned. Gaming continues to be an element of geek culture that struggles with stigmatization from more mainstream American culture.”

“That being said, I do think that we can go to a distraction too much,” she admits. “So, do I pay attention to things like frequency, or how often folks are playing games? Of course. But it’s not just about the number of hours. It’s also [about] exploring with whoever I’m working with: how are games helping? And how might they be hurting?”

Bean concurs: “One of the big things we need to focus on is: what’s the difference between immersion [and] high engagement [on the one hand] and the concept of what could possibly be considered an addiction [on the other]?”

Unfortunately, a lot of people continue to have strong opinions on the matter — opinions that are often not based on data or a proper understanding of gaming.

“Of the WHO’s people who created this diagnosis, the youngest was in their 40s or 50s,” Bean says, raising concerns about the ageist views the WHO board members may be taking towards gaming. Additionally, he continues, “They’re all researchers; they’re not clinicians. I don’t know if they’ve ever stepped into an actual therapeutic relationship with a client. A lot of clinicians do not agree that the diagnosis is [actually a] good [thing].”

“In the 5–10 years I’ve been doing this, I have yet to see anyone addicted to a game to the point where no matter what I do, or what interventions I do, they can’t stop playing,” says Bean. “Or they cannot reduce their playing time on some level.”

Conclusion

“Go into the world with open ideas, understand the culture, understand the video gamers, and pick up a damn game controller.”

Given the current zeitgeist, it might be some time until we see the widespread use of video games as therapeutic devices. Indeed, we’re likely still far off from hospitals widely issuing Nintendo Switches or Oculus Quests to patients — although there’s certainly precedent for using gaming in medical settings.

But moral panics are cyclical — they eventually die down as the reviled technology becomes more widely adopted and as the crusaders move on to something else to freak out over. This panic will be no different. Indeed, 65% of American adults already play video games, and the stigma amongst the general public around gaming is slowly eroding.

It will take the mental health community more time to catch up — not just in terms of accepting the very idea of games as therapy but also by creating effective parameters and boundaries for practitioners. Until that happens, games like Breath of the Wild (and its upcoming sequel) will continue to heal and comfort players in less official and formal ways; and practitioners like Garski and Bean will remain at the vanguard, imploring their colleagues to look at gaming from a different angle.

“Go into the world with open ideas, understand the culture, understand the video gamers, and pick up a damn game controller,” Bean urges his peers.

“This is just a natural offshoot of play therapy, which many of my colleagues are familiar with,” Garski insists. “Do we need to have parameters, and maybe even safeguards, on how they are to be used? Absolutely. But why would we want to walk away from something that means so much to so many of our clients, for whom playing these games has been a healing, transformative experience?”

“Why shut the door on that? What’s the harm?”

What’s the harm, indeed?

Special thanks to everyone who shared their stories with me on Reddit and Discord, Dr. Anthony Bean and Larisa Garski for so generously contributing their time and expertise for this piece, Nico Ryan for being such a great editor, and you for reading the whole article! May the Triforce be with you—all of you—and may your days be happy, hopeful, and healthy.

Jay Rooney is a lifelong Zelda fan, copywriter, marketing instructor, and father. His Switch code is SW-2888–2425–3008. If you like this post, check out his other Nintendo and Zelda articles — and remember to clap and/or share to spread the word!

This is a very cool article about how Zelda links to your mental health

👍